A monthly look at astronomical events in the sky and on Earth

Compiled and written by Steve Sawyer

Welcome to November What’s up!

As Bonfire Night come closer and the air gets crisp, we’re all familiar with fireworks lighting up our local skies. But did you know the cosmos puts on its own, much grander, fireworks display every single day?

This November, we’re diving into the mind-blowing world of cosmic explosions – the universe’s most powerful blasts that shape galaxies, forge elements, and keep astronomers on their toes.

We’ll explore what these cosmic bangs are, how we first spotted them, what mysteries they still hold, and what incredible discoveries are just around the corner.

But first…..

This Months and Upcoming York Astro Presentations

Upcoming events to put in your diary

| Date | Title | Speaker |

|---|---|---|

| 07/11/2025 | Everything You Might Want to Know About Nebulae | Robert Williams |

| 21/11/2025 | The Star of Bethlehem | Brad Gibson |

| 05/12/2025 | Christmas Lecture – The Euclid Mission | Dave Armeson |

For further details see the events page Astronomy Presentations by guest speakers | York Astro and our Facebook group (20+) The York Astronomical Society Chat Group | Facebook

So what’s on this month?

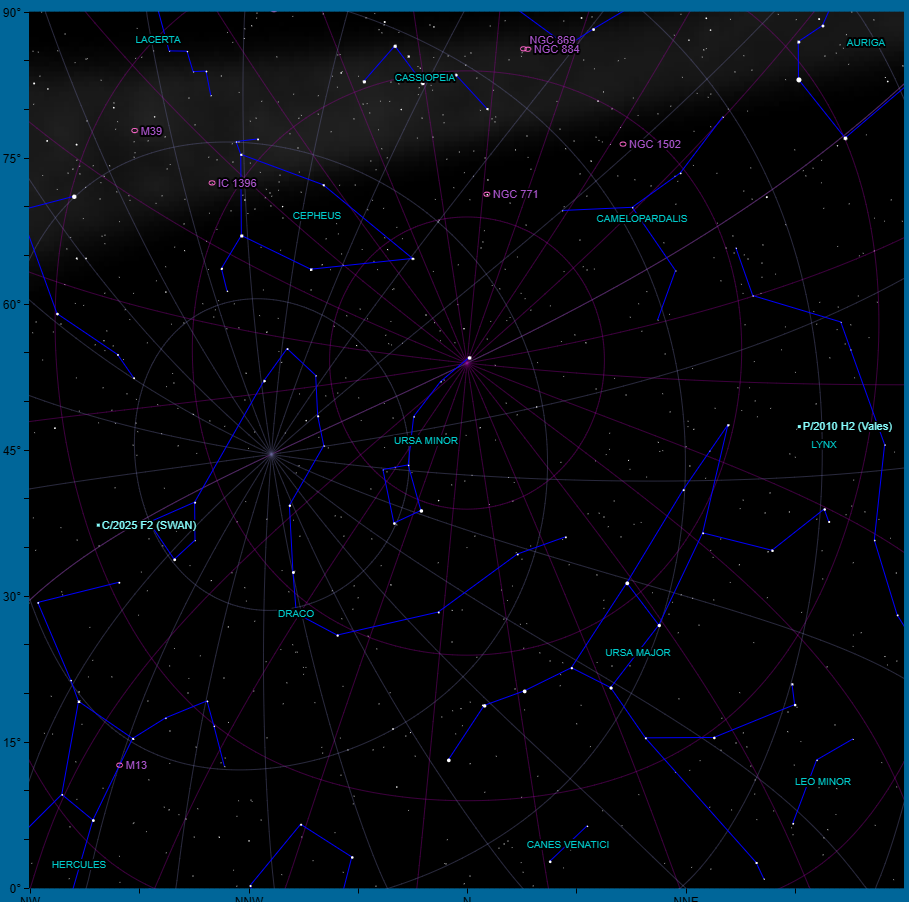

Northern Sky

Most of Aquila has now dipped below the horizon, but Vega in Lyra and Deneb in Cygnus two corners of the Summer Triangle are still shining in the western sky. Draco’s head sits low in the northwest, and only a sliver of Hercules remains. Ursa Major’s southern stars are beginning to rise.

The Milky Way arches high overhead thicker and more crowded to the west, thinning out through Auriga and Monoceros in the east. Cassiopeia is near the zenith now, with Cepheus drifting towards the northwest. Auriga is climbing high in the northeast, and Gemini, with Castor and Pollux, is well clear of the eastern horizon. Even Procyon is just peeking up due east.

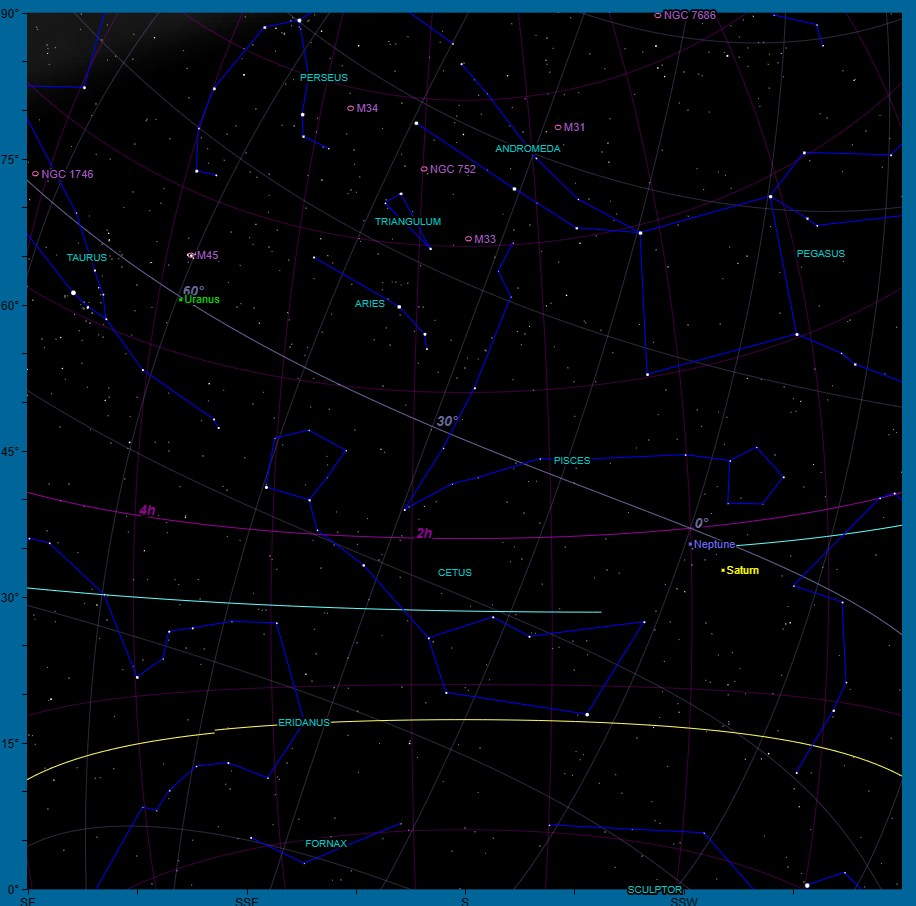

Southern Sky

Orion is now fully above the eastern horizon, and to its west, part of Eridanus that long, winding constellation starting near Rigel is visible. Higher up, Taurus is easy to spot with the Pleiades cluster and bright orange Aldebaran.

Over towards the meridian, Pisces and Cetus are well placed, along with the variable star Mira in Cetus, which is at a good height for observing right now. Capricornus has sunk out of sight, but Aquarius is still hanging on. Altair is just visible early on, though most of Aquila has gone. Delphinus, Sagitta, and Vulpecula are fading fast too.

Finally, Pegasus and Andromeda are both easy to find with one of Andromeda’s star chains stretching up towards the zenith, not far from a bright star in Perseus, now high in the eastern sky.

Sky Diary November 2025

This table captures the astronomical events for November, including phases of the moon, planetary alignments, and other notable occurrences.

| Date | Time (UTC) | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 02 | 01:02 | Venus (mag. –3.9) 3.3° north of Spica | Visible in the early morning sky. |

| 02 | 10:46 | Saturn (mag. 0.8) 3.7° south of the Moon | Morning event – pair low in the western sky. |

| 05 | 13:19 | Full Moon | The “Beaver Moon” – bright all night. |

| 05 | 22:29 | Moon at perigee – 356,833 km | Closest approach; expect larger tides and a slightly bigger Moon. |

| 06 | 15:26 | Pleiades 0.8° south of the Moon | Lovely evening pairing in Taurus. |

| 09 | 02:41 | Mercury (mag. 0.3) 2.6° north of Antares | Predawn view, low in the southeast. |

| 10 | 06:40 | Pollux 2.7° north of the Moon | Visible before dawn in the east. |

| 10 | 07:56 | Jupiter (mag. –2.4) 4.0° south of the Moon | Bright morning pairing – an easy naked-eye sight. |

| 12 | 05:28 | Last Quarter Moon | Rises after midnight; ideal for lunar observing. |

| 12 | — | Northern Taurid Meteor Shower – maximum | Expect a modest peak overnight; some bright fireballs possible. |

| 12 | 22:51 | Regulus 1.1° south of the Moon | Visible late evening. |

| 13 | 04:00 | Mercury (mag. 1.1) 1.2° south of Mars (mag. 1.5) | Early-morning conjunction – both low near dawn. |

| 17 | 10:11 | Spica 1.2° north of the Moon | Low in the southeast at dawn. |

| 17 | — | Leonid Meteor Shower – maximum | Active overnight 16th–17th; best viewed after midnight. |

| 20 | 02:48 | Moon at apogee – 406,693 km | Smallest and most distant Moon of the month. |

| 20 | 06:47 | New Moon | Dark skies for deep-sky observing. |

| 21 | 13:00 | Uranus at opposition (mag. 5.6) | Visible all night in Aries; binocular or small-scope target. |

| 23 | 11:00 | Mercury at perihelion | The planet reaches its closest point to the Sun. |

| 28 | 06:59 | First Quarter Moon | Evening half-Moon high in the south. |

| 29 | 19:08 | Saturn (mag. 0.9) 3.7° south of the Moon | Evening pairing, low in the southwest. |

Sky Maps

Looking South on the 15th at 22:00

Looking North on the 15th at 22:00

The two charts above show all DSOs of magnitude 6.0 or brighter. They are both taken from

SkyViewCafe.com and correct for the 15th of the month. For a clickable list of Messier objects with images, use the Wikipedia link.

Novembers Feature

Cosmic Explosions – When the Universe Lets Off Steam

Cosmic explosions aren’t just spectacular light shows; they’re the universe’s power plants, releasing incredible amounts of energy and scattering the ingredients for new stars, planets, and even life itself.

Think of it as a silent symphony of destruction and creation, playing out on a scale beyond our comprehension. These events aren’t random outbursts they’re vital parts of the cosmic life cycle, constantly recycling matter and energy across the universe.

Supernovae – The Grand Finale of Giant Stars

When a massive star runs out of fuel, gravity takes over and the star collapses in on itself. The result is a colossal explosion that can outshine an entire galaxy. These core-collapse supernovae leave behind neutron stars or black holes. Another type, known as Type Ia supernovae, happens when a white dwarf star in a binary system steals too much material from its companion and goes thermonuclear. These are so reliable in brightness that astronomers use them as “standard candles” to measure distances across the cosmos. Think of them as nature’s ultimate glitter bombs, scattering heavy elements like gold, silver and iron into space.

Gamma-Ray Bursts – The Universe’s Brightest Flashes

Gamma-ray bursts, or GRBs, are the most powerful explosions since the Big Bang. The long ones mark the death of huge stars collapsing into black holes, while the short bursts come from collisions between neutron stars. These cosmic crashes produce both flashes of gamma rays and ripples in spacetime gravitational waves that we can now detect on Earth.

Kilonovae – Where Gold is Forged

When two neutron stars merge, the resulting kilonova creates the heaviest elements in the periodic table: gold, platinum, uranium and more. So yes, the gold in your jewellery was once forged in a cosmic collision like this, billions of years ago.

Stellar Flares and Other Outbursts

Some stars release flares far more violent than those seen on our Sun. These “superflares” can batter nearby planets and strip away atmospheres a reminder of how lucky we are to orbit such a calm star. Smaller events, known as novae, come from white dwarfs that periodically erupt, while tidal disruption events occur when a black hole tears a passing star apart, lighting up the surrounding space.

So next time you look up at the night sky, remember that every atom of gold, iron, and oxygen both up there and within us was once part of one of these magnificent cosmic fireworks.

Glimpses from the Past — How Humanity First Spotted the Blasts

Human fascination with the heavens is ancient. Long before telescopes or satellites, early sky-watchers saw cosmic violence unfold with their own eyes. Chinese astronomers recorded mysterious “guest stars” such as SN 185 CE and SN 1006, the latter so bright it cast shadows on the ground. The Crab Nebula, visible in small telescopes today, is the glowing remnant of SN 1054, a spectacle that lit medieval skies without any optical aid.

Centuries later came the Renaissance revelations. Tycho Brahe’s 1572 nova and Kepler’s 1604 explosion shattered the long-held belief that the heavens were changeless. These were not “new stars” being born, but old ones dying spectacularly a shock to the philosophical order of the day.

The 20th century brought understanding and vocabulary. Astronomers realised that some novae were far more energetic than others and the word “supernova” was born. Then in 1987, the universe gave us SN 1987A, the first nearby supernova studied with modern technology. We had identified the star before it blew up, allowing theory and observation to meet for the first time. From Cold War satellites detecting gamma-ray bursts to realising those bursts came from collapsing giants and colliding neutron stars, we began to piece together the physics of cosmic cataclysms.

Even Type Ia supernovae turned out to be cosmic rulers measuring the universe’s expansion and leading to the startling revelation of dark energy. Those ancient bangs taught us not just where the elements come from, but how the cosmos itself grows.

What’s Exploding Today The Modern View

Our present-day understanding of stellar explosions is a patchwork of observation, theory, and humility. We’ve learned to read the distinctive “voices” of supernovae and gamma-ray bursts, mapping their environments and classifying their many flavours. Each one tells a different story of stellar death and rebirth.

Yet the universe keeps introducing new characters. Fast X-ray Transients (FXTs) brief bursts lasting mere minutes are now being traced back billions of years by telescopes like the Einstein Probe, giving us snapshots of the early universe. Extreme Nuclear Transients (ENTs) occur when supermassive black holes tear apart unlucky stars, producing eruptions brighter and longer-lived than any ordinary supernova cosmic indigestion on a grand scale.

Then there are the Fast Blue Optical Transients (FBOTs) such as The Cow (AT2018cow) dazzling, short-lived explosions that fade as quickly as they appear, defying easy classification. Add to that the discovery of rogue black holes devouring stars far from galactic centres, and it’s clear that the universe doesn’t like sticking to a script.

Why does this matter? Because every one of these events is a laboratory for extreme physics revealing how black holes grow, how elements form, and how galaxies evolve. When we study cosmic explosions, we’re watching the universe write its own autobiography.

Sparks, Debates, and Cosmic Riddles

Despite a century of progress, many mysteries remain.

The Supernova Simulation Problem: We understand the broad strokes of core-collapse explosions, but computers still struggle to reproduce the precise mechanism that re-energises the shockwave. Somewhere in the physics, a key ingredient is missing.

Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs): Those millisecond “pings” from deep space remain baffling. Why do some repeat while others are one-offs? Theories span from magnetars to more exotic possibilities, and the debate is fierce.

The Hubble Tension: Different methods of measuring cosmic expansion give different answers a major headache for cosmologists and perhaps a hint of new physics.

Unexplained X-ray Blasts: Events such as CDF-S XT1 resist classification. Are they new types of cataclysm or just peculiar variants of known ones?

And then there’s GRB 230307A, with its rhythmic “heartbeat” signal evidence that some long-duration gamma-ray bursts may be powered not by black holes, but by newborn, ultra-magnetic neutron stars (magnetars). Every discovery rewrites a chapter, and the universe keeps tossing curveballs.

Lighting Up the Future The Next Decade of Discovery

The coming years promise a golden age of transient astronomy.

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will be a true explosion hunter, expected to detect more than 100,000 new transients, from supernovae to kilonovae and perhaps even the deaths of the first stars. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory (LSST), armed with the largest astronomical camera ever built, will scan the entire southern sky every few nights, capturing millions of stellar outbursts and refining our grasp of dark energy.

The Einstein Probe, already operational, is providing near-real-time alerts on high-energy events, while missions like 4MOST and SVOM join the chase, ensuring no flash goes unnoticed.

The data deluge will be overwhelming far beyond human capacity to analyse unaided. Machine learning and AI are stepping in to sift the noise, flag the fleeting, and help us listen more closely to the universe’s whispers and shouts.

Meanwhile, theorists push models to their limits, simulating explosions that match what telescopes actually see. Others search for faint relic signals from the universe’s first instants echoes of creation itself. Every improvement in modelling or observation helps us map how matter, energy, and time intertwine. We’re not just spectators; we’re decoding the cosmic recipe itself.

Conclusion — Keep Looking Up and Listen for the Bangs

From ancient “guest stars” to cutting-edge AI, our quest to understand cosmic explosions has been nothing short of a revelation. They are not only spectacular they are the architects of everything we are. Each blast recycles matter, forges new elements, and seeds future generations of stars and planets.

So this November, as fireworks bloom across Bonfire Night skies, remember the far greater displays lighting up the galaxies the true cosmic pyrotechnics that shape the universe. Keep watching, keep wondering, and never stop listening for the next great bang.

Novembers Sky Guide

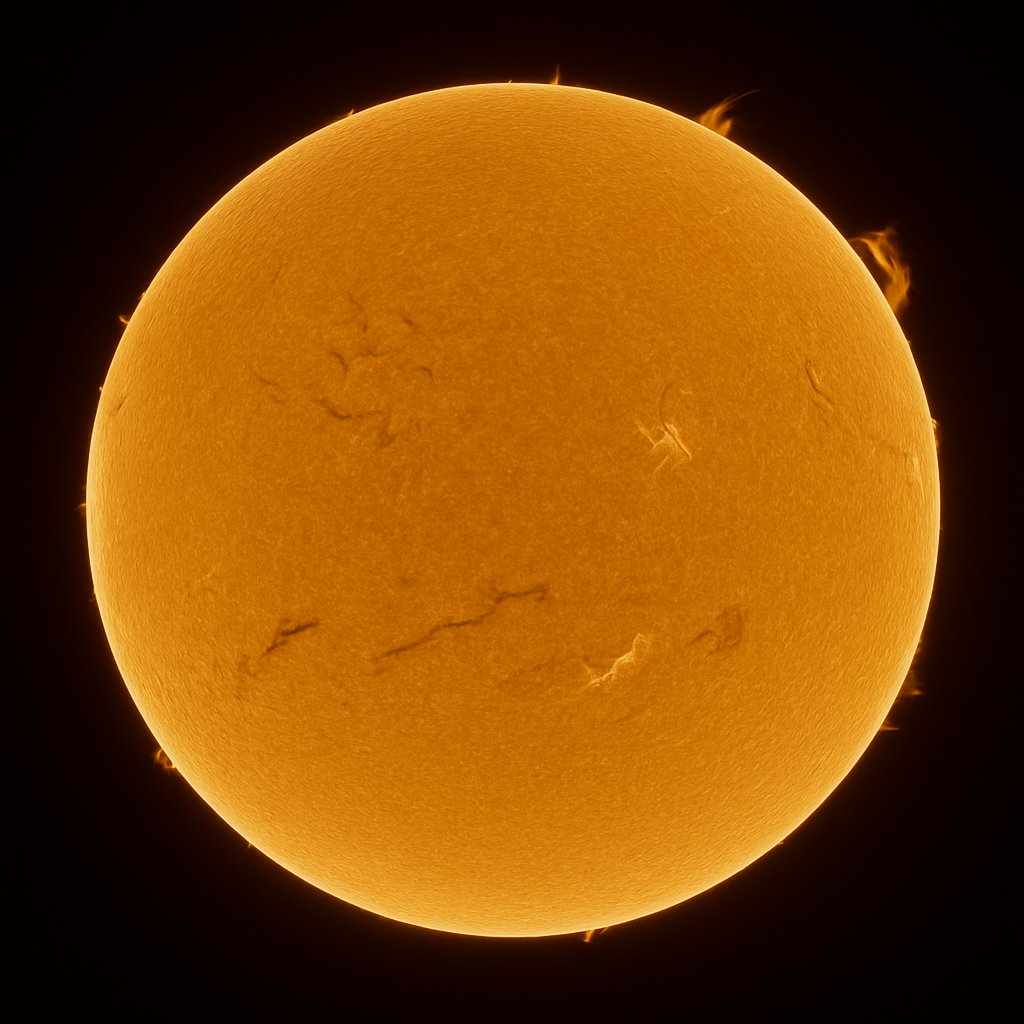

The Sun

☀️ Solar Forecast – November 2025

Solar activity looks fairly steady through late October into November, with a few bursts of geomagnetic unrest likely mid-month. The 10.7 cm solar radio flux (an indicator of solar activity) continues to climb gradually, suggesting more sunspot and flare potential as we approach the end of the solar cycle’s active phase.

Highlights:

- Late October: A couple of active days around 28–29 October (Kp up to 4), meaning aurora may be visible at higher latitudes if skies cooperate.

- Early November: Solar conditions quieten slightly, but remain lively, with flux values rising towards 140.

- 8–9 November: A period of increased activity, with the planetary A-index peaking near 20 and Kp values around 5 likely geomagnetic storm conditions.

- Mid-month: A calmer phase follows, though another spike is forecast around 15 November, possibly bringing another round of high-latitude aurora.

- Late November: Conditions settle again, with flux around 140–150 and a quiet geomagnetic environment.

📊 Summary Table

| Date | Solar Flux (10.7 cm) | Geomagnetic A Index | Max Kp | Activity Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 27–29 | 120 | 18 | 4 | Moderate geomagnetic activity possible aurora. |

| Oct 30–Nov 5 | 125–140 | 5–8 | 2–3 | Mostly quiet, stable conditions. |

| Nov 6–7 | 140–145 | 12 | 4 | Active region building, unsettled geomagnetic field. |

| Nov 8–9 | 145–150 | 18–20 | 5 | Strong geomagnetic disturbance – aurora possible! |

| Nov 10–14 | 155–175 | 5–8 | 2–3 | Calmer phase, flux increasing steadily. |

| Nov 15 | 175 | 12 | 4 | Isolated geomagnetic storm likely. |

| Nov 16–22 | 165–140 | 5–8 | 2–3 | Quiet end to the month. |

Auroa Forecasts

A bit US centred but still useful

Aurora Dashboard (Experimental) | NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center

And our own Met-office have an excellent space weather forecast page here Space Weather – Met Office

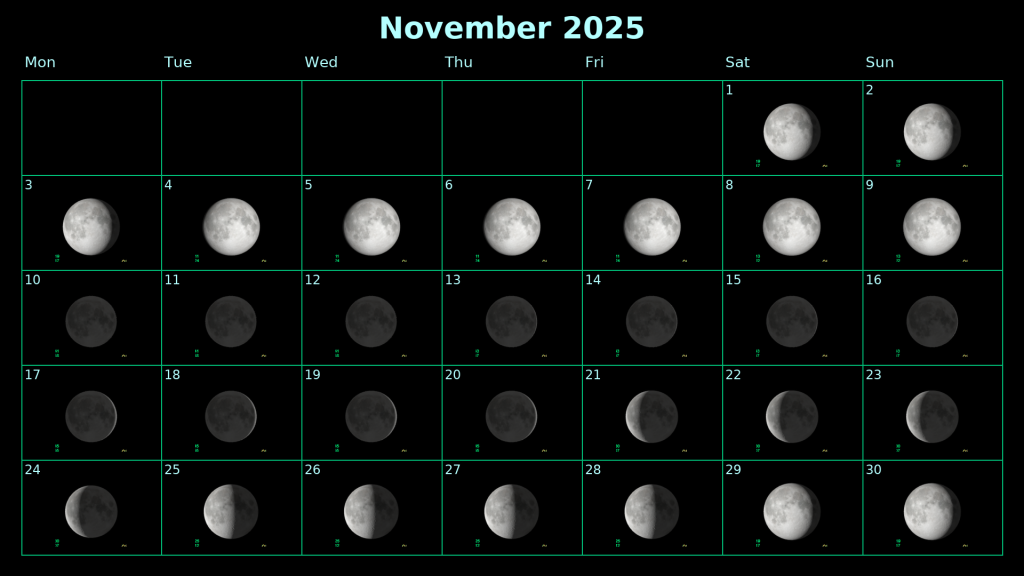

The Moon

November Lunar Calendar

Novembers moon calendar from Sky View Café (skyviewcafe.com)

A full yearly lunar calendar can be found here :-

https://www.mooninfo.org/moon-phases/2025.html

Moon Feature

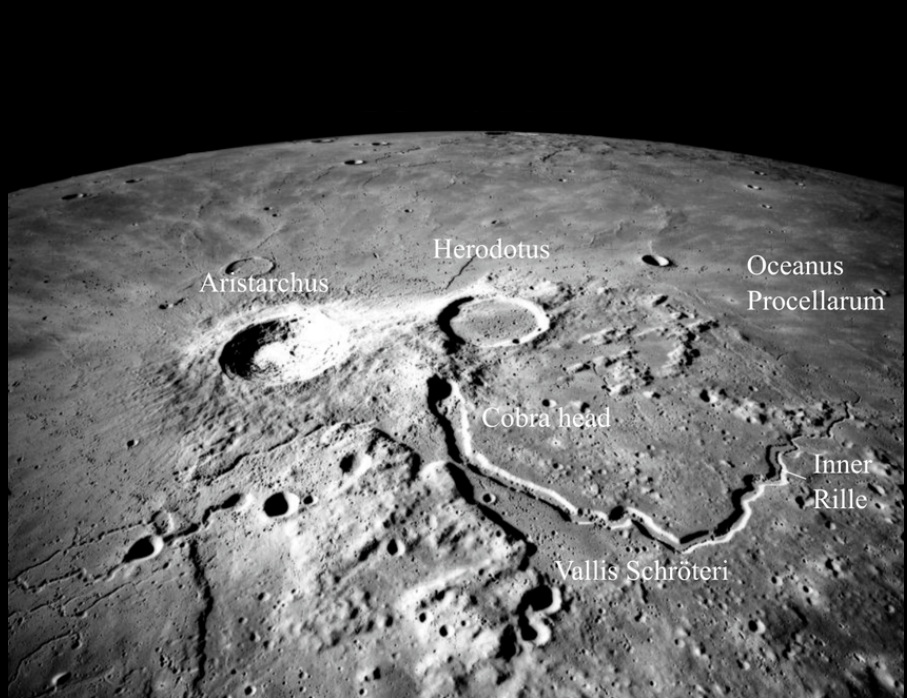

We’ve been to this region of the moon before, but we’re taking another look for different reasons other than pure aesthetics.

Aristarchus Plateau and Vallis Schröteri

Few features combine beauty, mystery, and scientific intrigue like the Aristarchus Plateau, located in the Moon’s northwest quadrant. It’s easily visible even through small telescopes, especially a few days after First Quarter when the terminator (the line dividing lunar day and night) runs close by.

It includes Aristarchus Crater one of the brightest spots on the Moon and the Cobra Head region at the mouth of Vallis Schröteri, the largest sinuous rille on the Moon. This region glows spectacularly because it’s rich in anorthosite and freshly exposed materials, which reflect sunlight intensely.

According to Brian Cudnik’s Encyclopedia of Lunar Science (Springer, 2023), the Aristarchus Plateau is geochemically unique: remote sensing shows unusually high concentrations of thorium, uranium, and potassium, as well as titanium-bearing basalts. These “KREEP” elements (Potassium, Rare Earth Elements, and Phosphorus) tell us this area preserves remnants of the Moon’s early magma ocean basically the frozen chemical leftovers of the lunar crust’s formation.

NASA’s Lunar Prospector and Chandrayaan-1 missions confirmed this enrichment, making Aristarchus a hotspot for future in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) studies.

Unusual Lunar Materials: Gold, Water, and Other Treasures

The Moon is chemically impoverished compared to Earth it’s missing volatile elements like hydrogen and carbon that escape easily in a vacuum but that doesn’t mean it’s valueless.

- Gold and precious metals: Trace amounts of gold, platinum, and palladium have been detected in Apollo samples, but only at parts-per-billion levels. These are likely relics of meteoritic impacts rather than indigenous veins so no El Dorado up there yet.

- Titanium and iron: Some maria, like Mare Tranquillitatis and Mare Imbrium, are rich in ilmenite (FeTiO₃) a titanium-iron oxide. This mineral is crucial for future lunar industry because it can yield oxygen and metal when processed.

- Helium-3: The solar wind has implanted significant quantities of this rare isotope in lunar regolith. It’s been suggested as a potential nuclear fusion fuel, though harvesting it remains more science fiction than business plan.

- Polar volatiles: Permanently shadowed craters at the lunar poles (especially Shackleton and Cabeus) contain water ice, carbon compounds, and possibly ammonia and methane, preserved for billions of years in perpetual darkness.

Planets

A bad day as a supernova shock wave hits the solar system, better cancel the milk 🙂

☀️ Mercury

Mercury is visible in the morning sky late in the month. It reaches inferior conjunction on 20 November, then reappears before sunrise — your best chance to spot it when it shines at magnitude –0.3.

🟡 Venus

Venus remains close to the Sun and is difficult to observe this month. At the start of November, it shines at magnitude –3.8 near Spica (Alpha Virginis), but it quickly disappears into solar glare.

🔴 Mars

Not visible

🟠 Jupiter

Jupiter dominates the night sky this month, shining brilliantly at magnitude –2.2 and reaching its highest point at 01:15 UT. Through a telescope, it shows a disk about 44 arcseconds across, with visible cloud bands and the Great Red Spot.

🪐 Saturn

Saturn is an evening object, visible in Aquarius. Its rings are nearly edge-on, making them appear very thin through a telescope. At magnitude +0.4, it sets around midnight.

🔵 Uranus

The faint planet Uranus is well placed for observation this month, reaching opposition on November 21st. It lies about 4.5° south of the Pleiades star cluster (M45), making it easier to find than in previous years. At a brightness of magnitude +5.6, Uranus is right on the edge of naked-eye visibility from dark-sky sites. With binoculars, it appears as a small greenish disk, while a telescope will reveal its planetary colour clearly. To resolve Uranus as a disk, use 100× magnification or more.

Larger telescopes (200mm+) and steady seeing conditions will allow you to detect faint atmospheric banding and subtle differences in hue. High-quality imaging setups can capture these contrasts better, especially with filters that enhance colour balance and reduce glare.

Uranus has five main moons visible in moderate to large telescopes — Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon. The brightest, Oberon, shines around magnitude +14.1, and Miranda, the faintest, around +16.4.

🔷 Neptune

Neptune remains visible in Pisces throughout November at magnitude +7.8. It’s too faint for naked-eye viewing but can be spotted easily with binoculars or a small telescope.

Meteor Showers

The Northern Taurids

The Taurid meteor stream drifts through our skies every year from late October into early December, peaking around 9 November 2025. While this shower never produces a torrent of meteors you might only see five or so per hour under dark skies. It’s worth stepping outside for one simple reason. The Taurids are renowned for their bright, slow-moving fireballs, long, graceful streaks that can rival Venus in brightness and occasionally cast shadows.

These meteors originate from debris shed by Comet Encke, one of the shortest-period comets known, looping around the Sun every 3.3 years. Over thousands of orbits, the comet’s trail has spread out across Earth’s path, creating a broad but sparse stream. This year, the shower’s timing comes just after the Full Moon on 5 November, which means lunar glare will wash out the faintest streaks. Still, because Taurids are often dazzlingly bright, some will punch through the moonlight.

Look toward Taurus, which rises in the east during the evening and climbs high through the night. There’s no need for telescopes or binoculars just wrap up warm, recline, and let your eyes roam.

The Leonids

The Leonids, active from early November to early December, will peak on the night of 17–18 November. This famous shower has a storied past in 1833 and 1966 it unleashed meteor “storms” numbering tens of thousands of streaks per hour. While no such tempest is expected this year, the Leonids remain one of the more reliable mid-November displays, offering 10–15 meteors per hour under ideal dark conditions.

The Leonids come from the dust trail of Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, which completes an orbit of the Sun every 33 years. Each tiny grain we see blazing through our atmosphere at around 70 km/s is a leftover from that comet’s wake. They’re fast, sharp, and often leave persistent trains that linger for seconds.

For us Northerners, the radiant lies in Leo, which rises after midnight. The best viewing window is from around 1 am until dawn, facing east or northeast. This year the Moon will be in a waning gibbous phase, so darker periods before moonrise or after moonset will be best for spotting fainter trails

Comets

| Comet Name | Predicted Magnitude | Visibility Period (Approx.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) | 4 | Early to Mid-November | Brightest of the month, good binocular target |

| C/2025 R2 (SWAN) | 8 | Throughout November | Diffuse, medium-bright comet in morning skies |

| 210P/Christensen | 8 | Early November | Short-period comet, faint and low in the sky |

| 24P/Schaumasse | 10 | Mid to Late November | Faint returning visitor, steady magnitude |

| C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) | 10 | Entire Month | Moderate magnitude, interesting trajectory |

| 240P/NEAT | 12 | Late November | Very faint, telescopic object |

| C/2022 N2 (PanSTARRS) | 13 | Whole Month | Persistent faint comet, near 13th magnitude |

| C/2024 E1 (Wierzchos) | 9 | Early November | Slightly brighter, good for astrophotography |

| C/2025 T1 (ATLAS) | 11 | Mid-November | Newly discovered, faint but photogenic |

| 3I/2025 N1 (ATLAS) | 11 | Mid-November | Interstellar object candidate — of great scientific interest |

C/2025 A6 (Lemmon)

Currently the brightest comet of the month, C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) is expected to hover around magnitude 4, possibly bright enough for naked-eye viewing from dark rural sites. Best observed during the first half of November, it will likely appear as a softly glowing fuzzball through binoculars. The Lemmon series of comets has a long history of producing photogenic tails, and this year’s visitor may continue that tradition. Look for it low in the pre-dawn sky, climbing gradually as it moves away from the Sun.

C/2025 R2 (SWAN)

A graceful visitor from the outer solar system, Comet SWAN should maintain a modest brightness near magnitude 8, visible with small telescopes. Although diffuse, it may reveal a pale greenish hue in long exposures — a sign of vaporising diatomic carbon. Active throughout the month, SWAN is best seen in morning twilight, tracing a gentle arc through the constellation Leo as it retreats into deeper space.

210P/Christense

A faint, short-period comet returning roughly every 6.5 years, 210P/Christensen remains an object mainly for telescope owners. Its brightness near magnitude 8 in early November makes it a subtle challenge for observers under dark skies. Historically, Christensen’s comets exhibit periodic outbursts, so it’s worth checking for unexpected surges in brightness — the kind that reward persistence on cold November nights.

24P/Schaumasse

This comet, a familiar sight to veteran observers, returns about every 8.2 years. With an expected magnitude around 10, 24P/Schaumasse will be faint but steady — a good photographic target for longer exposures. Passing through Cancer and Leo, its diffuse coma will appear like a small smudge against the star field. It’s one of those comets that repays patience and precise tracking.

C/2025 K1 (ATLAS)

A long-period comet likely from the Oort Cloud, C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) is visible through most of November with brightness fluctuating around magnitude 10. ATLAS comets have a reputation for unpredictable behaviour — some fade quietly, others flare spectacularly. This one is currently stable and a pleasing sight through moderate telescopes. Look for a faint tail in early evening skies.

C/2024 E1 (Wierzchos)

Named after the prolific comet discoverer Kacper Wierzchos, this faint yet rewarding comet should linger around magnitude 9. Under dark northern skies, it can be captured photographically as a bluish-green puff near the constellation Gemini. It’s likely to fade through the month, but its subtle charm appeals to observers chasing lesser-known comets.

C/2025 T1 (ATLAS

A newcomer discovered earlier in the year, C/2025 T1 (ATLAS) is expected to reach magnitude 11 by mid-November. Though faint, it’s an intriguing object for comet enthusiasts — particularly given its high inclination and dynamic orbital path. Its long tail may emerge in deep stacked images. For those imaging under dark skies, it’s worth tracking before dawn near Virgo.

240P/NEAT

At magnitude 12, 240P/NEAT is faint and requires a telescope with at least 8-inch aperture and dark-sky conditions. Despite its low brightness, it’s a classic target for those logging returning comets, offering a diffuse glow barely above the threshold of perception. Patience and dark adaptation are key.

C/2022 N2 (PanSTARRS)

This comet has been visible for much of 2025, now fading toward magnitude 13. It remains of interest primarily for astrophotographers and data gatherers. Although visually unimpressive, PanSTARRS comets are valuable scientifically, contributing to our understanding of volatile ices and dust composition in medium-period comets.

3I/2025 N1 (ATLAS)

If early reports hold, 3I/2025 N1 (ATLAS) could be only the third confirmed interstellar object after ‘Oumuamua and Borisov. With an estimated brightness around magnitude 11, it will appear faint but holds immense scientific significance. Its hyperbolic trajectory suggests an origin beyond our solar system, and astronomers worldwide are preparing to track its path across Perseus. For visual observers, catching even a hint of its motion against the stars is to glimpse something truly alien passing through our celestial backyard.

Link here for further details of each comet and how to locate it.

Visual Comets in the Future (Northern Hemisphere) (aerith.net)

Deep Sky (DSO’s)

A supa novae explodes in a distant galaxy far far away

Andromeda Galaxy (M31)

High above on clear November evenings in northern UK skies, the Andromeda Galaxy glows as a faint, elongated mist of light. Even binoculars reveal its shape and hints of its spiral arms. Use the “W” of Cassiopeia as a guide-post, then hop toward Mirach and onward to this distant island of a trillion stars. Under dark skies it’s a show-piece.

Orion Nebula (M42)

Although more prominent in winter, the Orion Nebula begins to rise into view during November nights. Nestled beneath Orion’s Belt in the “sword” region, this vivid star-forming cloud glows with pink and red gas. Even with modest telescopes or binoculars you’ll see a nebula of wonder — a peek into stellar birth.

Double Cluster (NGC 869 & NGC 884)

In the constellation Perseus, two rich open star clusters lie side-by-side, offering a dazzling star-field even through binoculars. In November the pair climbs higher in the night sky, inviting observers to pause and gaze into a rich tapestry of young stars, perfect for crisp nights in the countryside.

Triangulum Galaxy (M33)

A quieter companion to the Andromeda Galaxy, the Triangulum Galaxy is a faint spiral that rewards patience. Under good dark conditions it appears as a large, diffuse smudge through binoculars and a pattern of spiral structure through a telescope. It’s a fine target for November’s darker hours.

Dumbbell Nebula (M27)

The Dumbbell is one of the brightest planetary nebulae in the sky, shaped like a small hourglass. In November it’s still accessible with small scopes and even binoculars from dark sites. Its glowing shell around a dying star invites reflection on cosmic cycles.

Whirlpool Galaxy (M51)

Visible in the northern sky, the Whirlpool Galaxy presents itself as a faint and graceful spiral with a companion galaxy attached. It’s more challenging under UK skies, but November offers long viewing hours and if your skies are dark and steady it can be a rewarding sight.

NGC 362 (Globular Cluster)

Globular clusters are dense balls of ancient stars; NGC 362 is among the more accessible in November. A small telescope will begin to resolve its stars and you’ll sense the depth and age in its golden-hued core. A great complement to galaxies-and-nebula picks.

Heart Nebula (IC 1805)

This large emission nebula spans a broad area and glows with reddish hydrogen alpha light. From UK latitudes in November, a wide-field telescope or camera is best. The star field around it adds context and beauty. Patience and darkness reward you here.

NGC 4945 (Galaxy)

A more advanced target: this edge-on spiral galaxy lies in the southern skies from UK and demands a telescope and dark horizon. But its dust lanes and core structure make it a treat for those seeking something beyond the “easy” list.

Silver Sliver Galaxy (NGC 253)

Low in the southern sky for UK observers, this galaxy is best viewed from a site with clear southern horizon. With darkness and a mid-sized telescope, you’ll pick up the long, thin shape and subtle brightness variations — a fine challenge for November.

ISS and other orbiting bits

🚀 ISS Overpasses

| Date | Brightness (mag) | Start Time | Start Alt | Start Az | Highest Time | Highest Alt | Highest Az | End Time | End Alt | End Az | Visibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 Nov | -2.0 | 05:14:21 | 19° | SSW | 05:14:21 | 19° | SSW | 05:16:40 | 10° | SSE | Visible | |

| 02 Nov | -1.1 | 04:28:30 | 14° | SSE | 04:28:30 | 14° | SSE | 04:29:06 | 10° | SSE | Visible | |

| 14 Nov | -1.4 | 17:58:18 | 10° | S | 17:59:28 | 13° | SSE | 17:59:28 | 13° | SSE | Visible | |

| 15 Nov | -1.6 | 18:44:37 | 10° | SW | 18:45:59 | 20° | SSW | 18:45:59 | 20° | SSW | Visible | |

| 16 Nov | -2.2 | 17:56:32 | 10° | SSW | 17:59:13 | 23° | SSE | 17:59:30 | 23° | SE | Visible | |

| 16 Nov | -0.4 | 19:32:17 | 10° | WSW | 19:32:24 | 11° | WSW | 19:32:24 | 11° | WSW | Visible | |

| 17 Nov | -1.7 | 17:08:38 | 10° | S | 17:10:53 | 17° | SE | 17:12:57 | 11° | ESE | Visible | |

| 17 Nov | -2.1 | 18:43:52 | 10° | WSW | 18:45:51 | 29° | SW | 18:45:51 | 29° | SW | Visible | |

| 18 Nov | -2.9 | 17:55:30 | 10° | SW | 17:58:36 | 36° | SSE | 17:59:13 | 33° | SE | Visible | |

| 18 Nov | -0.4 | 19:31:47 | 10° | W | 19:32:07 | 12° | WSW | 19:32:07 | 12° | WSW | Visible | |

| 19 Nov | -2.4 | 17:07:11 | 10° | SW | 17:10:07 | 29° | SSE | 17:12:33 | 13° | E | Visible | |

| 19 Nov | -2.3 | 18:43:14 | 10° | WSW | 18:45:26 | 36° | SW | 18:45:26 | 36° | SW | Visible | |

| 20 Nov | -3.3 | 17:54:41 | 10° | WSW | 17:57:57 | 51° | S | 17:58:43 | 41° | SE | Visible | |

| 20 Nov | -0.4 | 19:31:13 | 10° | W | 19:31:36 | 13° | W | 19:31:36 | 13° | W | Visible | |

| 21 Nov | -3.0 | 17:06:10 | 10° | WSW | 17:09:22 | 43° | SSE | 17:11:58 | 14° | E | Visible | |

| 21 Nov | -2.3 | 18:42:35 | 10° | W | 18:44:51 | 37° | WSW | 18:44:51 | 37° | WSW | Visible | |

| 22 Nov | -3.5 | 17:53:57 | 10° | WSW | 17:57:14 | 58° | S | 17:58:04 | 42° | SE | Visible | |

| 22 Nov | -0.4 | 19:30:36 | 10° | W | 19:30:57 | 12° | W | 19:30:57 | 12° | W | Visible | |

| 23 Nov | -3.3 | 17:05:18 | 10° | WSW | 17:08:35 | 56° | S | 17:11:18 | 14° | E | Visible | |

| 23 Nov | -2.2 | 18:41:52 | 10° | W | 18:44:10 | 35° | WSW | 18:44:10 | 35° | WSW | Visible | |

| 24 Nov | -3.3 | 17:53:08 | 10° | W | 17:56:25 | 53° | S | 17:57:24 | 37° | SE | Visible | |

| 24 Nov | -0.3 | 19:29:58 | 10° | W | 19:30:17 | 12° | W | 19:30:17 | 12° | W | Visible | |

| 25 Nov | -3.3 | 17:04:24 | 10° | W | 17:07:42 | 58° | S | 17:10:39 | 12° | ESE | Visible | |

| 25 Nov | -2.0 | 18:41:06 | 10° | W | 18:43:33 | 29° | SW | 18:43:33 | 29° | SW | Visible | |

| 26 Nov | -2.7 | 17:52:17 | 10° | W | 17:55:26 | 40° | SSW | 17:56:51 | 25° | SE | Visible | |

| 26 Nov | -0.3 | 19:29:44 | 10° | WSW | 19:29:44 | 10° | WSW | 19:29:44 | 10° | WSW | Visible | |

| 27 Nov | -2.9 | 17:03:27 | 10° | W | 17:06:42 | 48° | SSW | 17:09:56 | 10° | ESE | Visible | |

| 27 Nov | -1.4 | 18:40:27 | 10° | W | 18:42:56 | 19° | SSW | 18:43:07 | 19° | SSW | Visible | |

| 28 Nov | -1.7 | 17:51:25 | 10° | W | 17:54:14 | 25° | SSW | 17:56:36 | 13° | SSE | Visible | |

| 29 Nov | -2.1 | 17:02:26 | 10° | W | 17:05:30 | 33° | SSW | 17:08:32 | 10° | SE | Visible | |

| 29 Nov | -0.6 | 18:40:59 | 10° | SW | 18:41:28 | 10° | SW | 18:41:57 | 10° | SSW | Visible | |

| 30 Nov | -0.8 | 17:50:50 | 10° | WSW | 17:52:48 | 15° | SW | 17:54:46 | 10° | S | Visible |

Useful Resources

StarLust – A Website for People with a Passion for Astronomy, Stargazing, and Space Exploration.

http://www.n3kl.org/sun/noaa.html

http://skymaps.com/downloads.html

Astronomy Calendar of Celestial Events 2024 – Sea and Sky (seasky.org)

https://www.constellation-guide.com

IMO | International Meteor Organization

and of course the Sky at Night magazine!