A monthly look at astronomical events in the sky and on Earth

Compiled and written by Steve Sawyer

An artistic impression of The giant radio galaxy Inkathazo (32× size of Milky Way, discovered with MeerKAT)

Radio Astronomy part 1

This month we turn our gaze not to the visible sky, but to the hidden universe revealed by radio astronomy. Where optical telescopes see stars and galaxies shining in light, radio telescopes uncover the cold gas between stars, the jets of black holes, the signals of pulsars, and mysterious bursts from across the cosmos.

But radio astronomy isn’t just about powerful dishes it’s also about powerful data. Modern arrays produce vast amounts of information that no human could ever sift through alone.

That’s where AI and big data step in. Machine learning and AI are becoming a crucial tool for discovery.

This October, as we enjoy long, clear nights (hopefully) under Orion’s rising stars, we’ll also explore how radio astronomers are using the invisible spectrum and artificial intelligence to open new windows on the universe.

And if the weather turns out to be rubbish looking and analysing data produced by radio telescopes can be an interesting hobby in itself.

There’s even an open source radio telescope you can use for free :-

PICTOR: A free-to-use Radio Telescope

Welcome to Octobers What’s up!

Welcome to October the month where the night finally returns in full. For those of us in the northern UK, the long summer twilight is firmly behind us, and we’re now treated to genuinely dark skies before most people have even had their tea. With the clocks going back on the 26th, evenings will feel noticeably longer, giving us a head start on the night’s astronomical offerings.

This is one of the best times of year to step outside and look up. The air is cooler and often clearer, with crisp nights that make stars appear extra sharp just remember to grab a coat and maybe a warm drink. The Summer Triangle (Vega, Deneb and Altair) still hangs high in the southwest at the start of the evening, but it’s slowly giving way to the autumn and early winter constellations.

We’ve also got some cosmic treats this month: the Orionid meteor shower is active, peaking around the 21st, and comet C/2023 A3 Tsuchinshan–ATLAS might still offer a decent view near sunset, depending on how it’s faring post-perihelion.

Here’s what’s up this month!

This Months and Upcoming York Astro Presentations

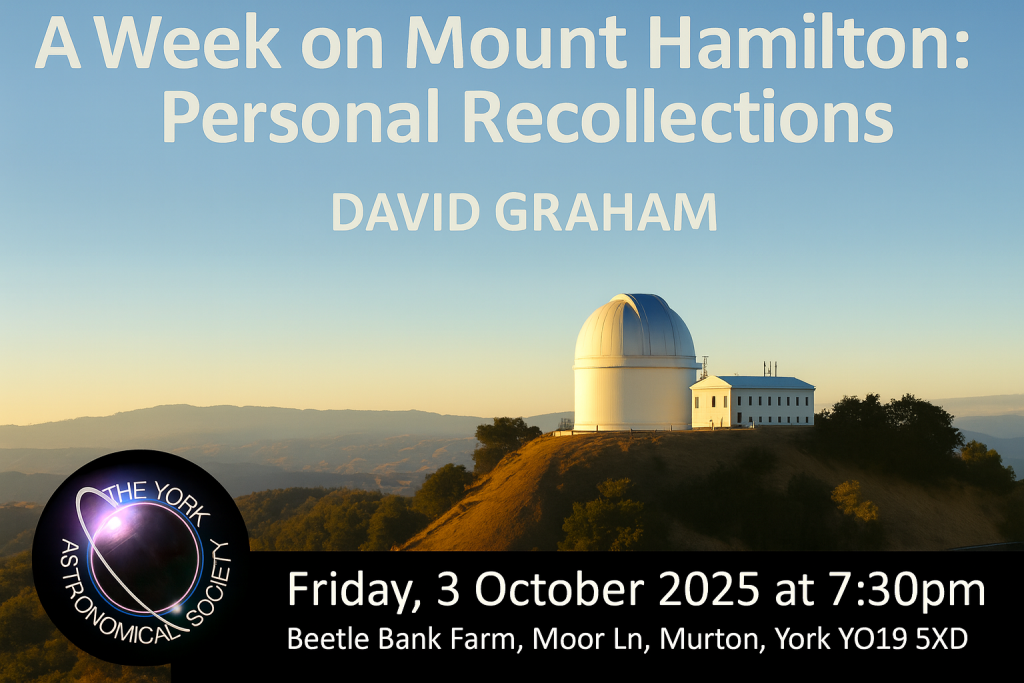

Upcoming events to put in your diary

| Date | Title | Speaker |

|---|---|---|

| 03/10/2025 | A Week on Mount Hamilton: Personal Recollections | David Graham |

| 17/10/2025 | Annual General Meeting + Short Talks | YAS Members |

| 07/11/2025 | Everything You Might Want to Know About Nebulae | Robert Williams |

For further details see the events page Astronomy Presentations by guest speakers | York Astro and our Facebook group (20+) The York Astronomical Society Chat Group | Facebook

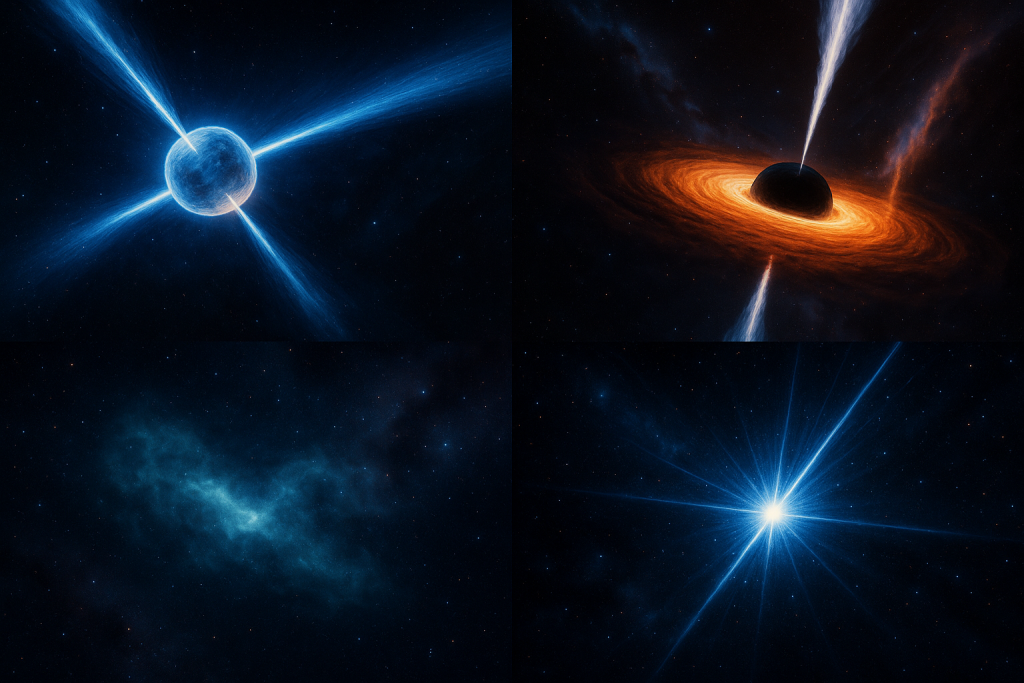

Radio astronomy impressions

Radio Astronomy Part 2

What is Radio Astronomy?

When most of us think of astronomy, we picture gleaming telescopes pointed at the night sky, collecting light from stars and galaxies. But visible light is only a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum including: high-energy gamma rays to long, invisible radio waves. Radio astronomy is the branch of science that studies the universe using these radio waves.

Instead of mirrors and lenses, radio telescopes use giant dish antennas to “listen” to the cosmos. These signals are incredibly faint often weaker than the static from a mobile phone but they carry a wealth of information that optical telescopes can’t reveal. Through radio astronomy we’ve discovered:

Pulsars rapidly spinning neutron stars that sweep beams of radio waves past Earth like lighthouse beacons.

Cold hydrogen gas the raw material of galaxies, invisible to optical telescopes but glowing faintly in radio at a wavelength of 21 centimetres.

Jets from black holes enormous streams of charged particles launched at near-light speed, stretching across millions of light-years.

Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) mysterious, millisecond flashes of radio energy from deep space, whose origins are still being unravelled.

What makes radio astronomy so powerful is its ability to show us the hidden universe the cold, the energetic, and the transient. It’s a reminder that the night sky is far richer than what our eyes alone can see.

So what’s on this month?

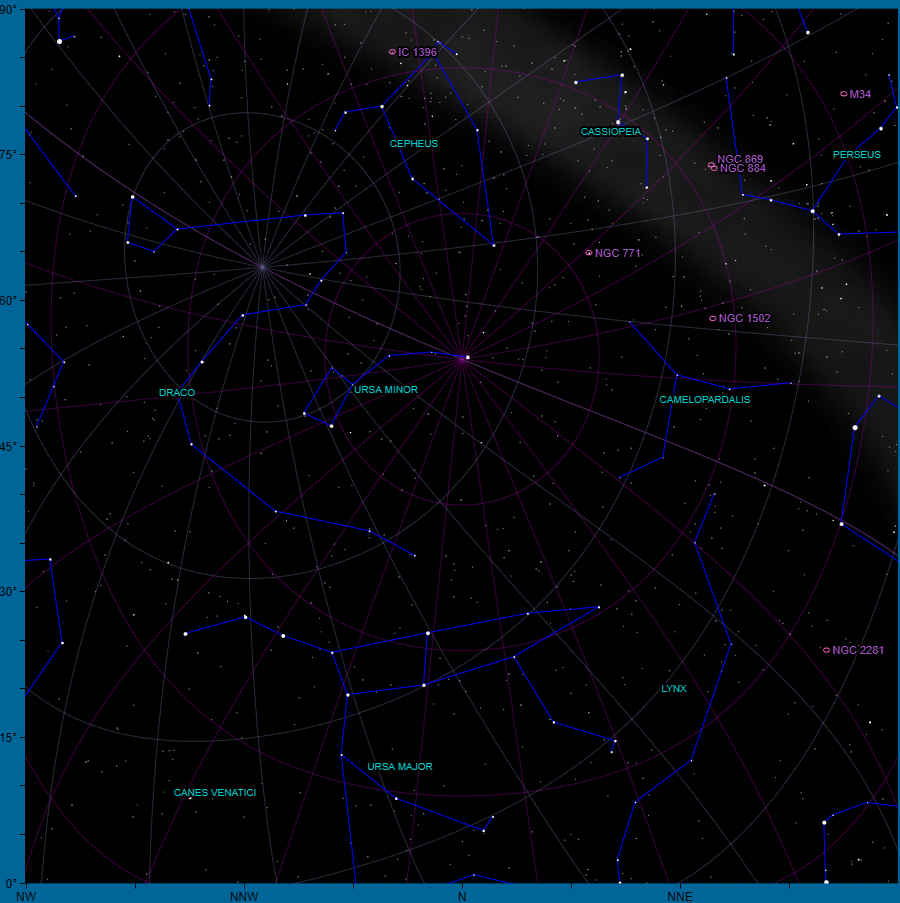

As October settles in, the night sky shifts into its autumn character. Ursa Major now hugs the northern horizon, while high overhead, Cepheus, Cassiopeia, and Perseus frame the Milky Way near the zenith. To the east, Auriga, Taurus, and the glittering Pleiades are rising, joined by Aldebaran glowing orange in the Hyades cluster.

Orion and Gemini begin to clear the eastern horizon late in the evening — early signs that winter constellations are on their way. Meanwhile, Boötes, Corona Borealis, and Hercules sink out of view in the northwest, and Aquila and Altair from the Summer Triangle drift lower in the western sky.

Looking south, the Great Square of Pegasus stands out, flanked by the stars of Pisces, with Alrescha marking the “knot” where its twin lines meet. Below lies Cetus, and further east, Aquarius is well placed, with Fomalhaut shining low near the southern horizon.

The Milky Way still puts on a show, running from Cygnus in the west through Vulpecula, Sagitta, and Aquila. Between the Milky Way and Pegasus sit the small constellations Delphinus and Equuleus. In the southeast, Andromeda and Triangulum are high, with Aries below them. Perseus, Taurus, and the Pleiades climb steadily in the east, and by late evening, Orion makes his seasonal return.

Sky Diary

This table captures the astronomical events for October, including phases of the moon, planetary alignments, and other notable occurrences.

October 2025 Astronomy Calendar

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 2nd | Venus at perihelion |

| 3rd | Dwarf planet Ceres at opposition (mag. 7.6) |

| 6th | Saturn close to the Moon |

| 7th | Full Moon |

| 8th | Moon at perigee (closest to Earth) |

| 10th | Moon near the Pleiades |

| 10th | Southern Taurid meteor shower peak |

| 13th | Last Quarter Moon |

| 13th | Jupiter and Pollux close to the Moon |

| 16th | Moon near Regulus |

| 19th | Mercury close to Mars; Venus close to the Moon |

| 21st | New Moon |

| 22nd | Orionid meteor shower peak |

| 23rd | Moon near Mercury; Moon at apogee (farthest from Earth) |

| 25th | Moon near Antares |

| 29th | First Quarter Moon |

| 29th | Mercury at greatest elongation east |

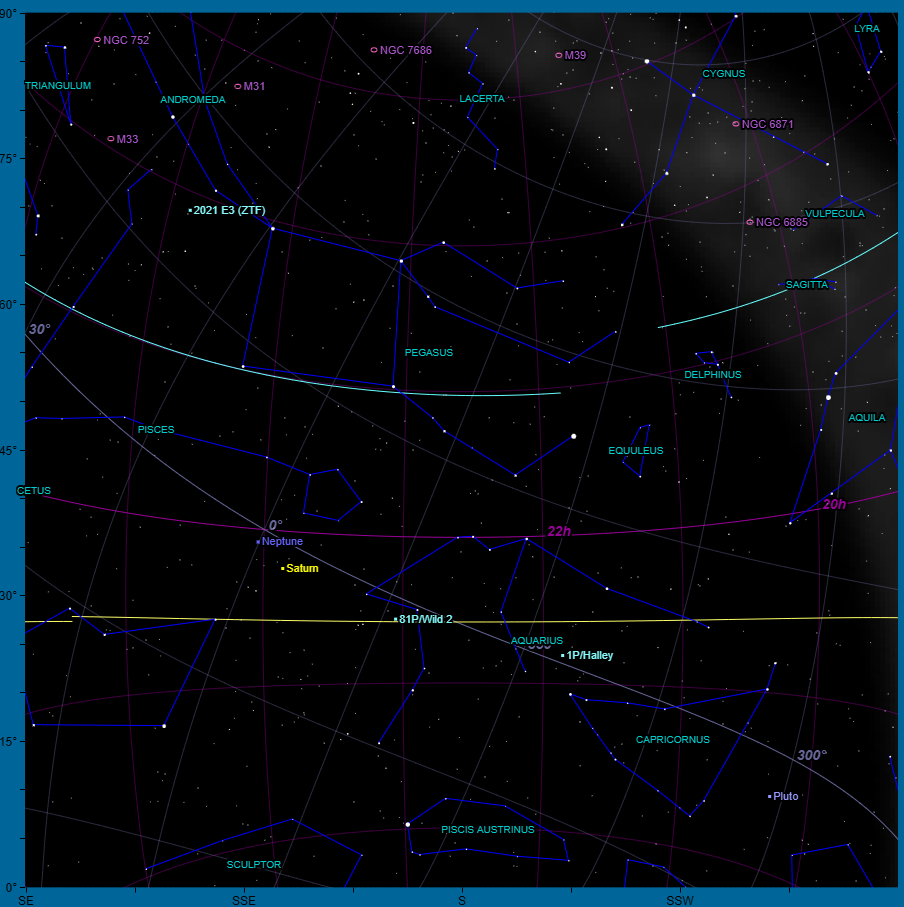

Sky Maps

Looking South on the 15th at 22:00

Looking North on the 15th at 22:00

he two charts above show all DSOs of magnitude 6.0 or brighter. They are both taken from

SkyViewCafe.com and correct for the 15th of the month. For a clickable list of Messier objects with images, use the Wikipedia link.

Octobers Objects

Radio Astronomy Part 3

Recent Discoveries

Radio astronomy is one of the most dynamic fields in modern science, and in just the past year it has produced discoveries that continue to reshape our understanding of the universe.

One headline grabber is the giant radio galaxy Inkathazo, discovered with the MeerKAT telescope in South Africa. Its plasma jets stretch an incredible 32 times the size of the Milky Way, making it one of the largest single structures ever seen. Objects like Inkathazo help astronomers understand how supermassive black holes launch and sustain such enormous outflows across intergalactic space.

Recently India’s upgraded Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (uGMRT) detected a rare millisecond pulsar in the globular cluster M80. This tightly packed swarm of ancient stars has now revealed a neutron star spinning hundreds of times per second. Its extreme orbit makes it a natural laboratory for testing Einstein’s theory of general relativity under intense gravitational conditions.

And in March 2025, the CHIME radio telescope’s new Outrigger stations pinpointed the origin of a nearby fast radio burst (FRB) a mysterious millisecond flash of radio energy. This burst came from the galaxy NGC 4141, only about 130 million light-years away, making it one of the closest FRBs ever localised. Each discovery adds a vital piece to the puzzle of what drives these powerful cosmic flashes.

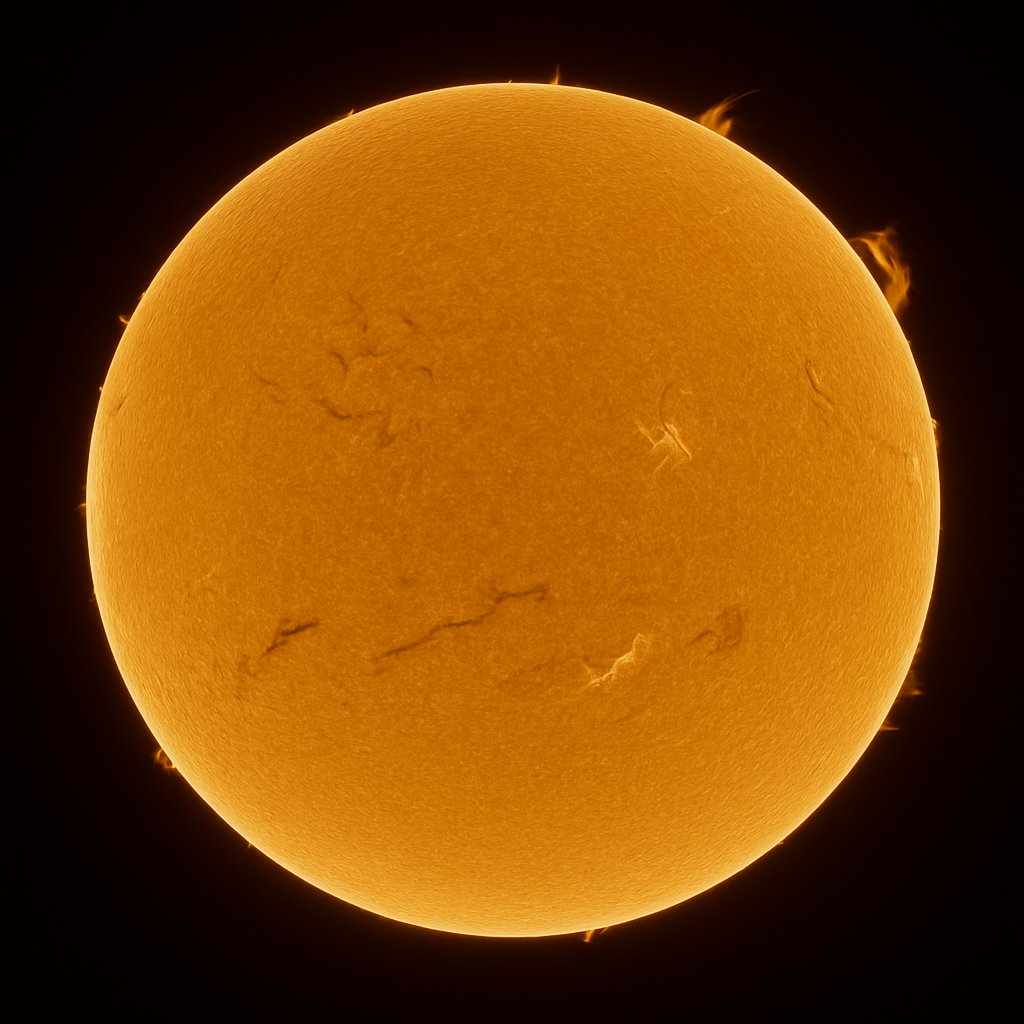

The Sun

☀️ October 2025 Solar Forecast

Highlights for October

- Early October (1st–10th): The Sun is moderately active, with radio flux values around 155–180. Geomagnetic conditions are mostly quiet, though the 3rd–4th could see unsettled activity (Kp 3–4).

- 11th–12th: A spike in geomagnetic activity is forecast, with the Kp reaching 5 on the 11th a chance for aurora sightings if skies are clear.

- Mid-Month (13th–18th): Solar activity dips slightly (flux ~140–155) with generally quiet geomagnetic conditions (Kp 2).

- 19th–20th: Another burst of activity expected, with flux climbing back to ~160 and Kp reaching 5 on the 20th another aurora opportunity.

- Late October (21st–25th): The Sun settles again with flux ~150–165. A moderate disturbance on the 25th could bring Kp 4.

📊 October Solar Activity Table

| Date Range | Solar Activity (10.7 cm Flux) | Geomagnetic Outlook | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st–2nd | 175–180 | Quiet (Kp 2) | Stable conditions |

| 3rd–4th | 170 | Unsettled (Kp 3–4) | Minor geomagnetic activity possible |

| 5th–10th | 155–165 | Quiet (Kp 2–3) | Generally calm |

| 11th–12th | 145 | Active (Kp 4–5) | Potential aurora at mid-latitudes |

| 13th–18th | 140–155 | Quiet (Kp 2) | Low solar activity |

| 19th–20th | 160 | Active (Kp 4–5) | Increased chance of aurora |

| 21st–24th | 155–165 | Quiet to unsettled (Kp 2–3) | Mostly calm |

| 25th | 150 | Unsettled (Kp 4) | Minor storming possible |

✨ In summary: 11th–12th and 19th–20th October are the best bets for aurora watchers in the northern UK, provided the weather cooperates.

Auroa Forecasts

A bit US centred but still useful

Aurora Dashboard (Experimental) | NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center

And our own Met-office have an excellent space weather forecast page here Space Weather – Met Office

The Moon

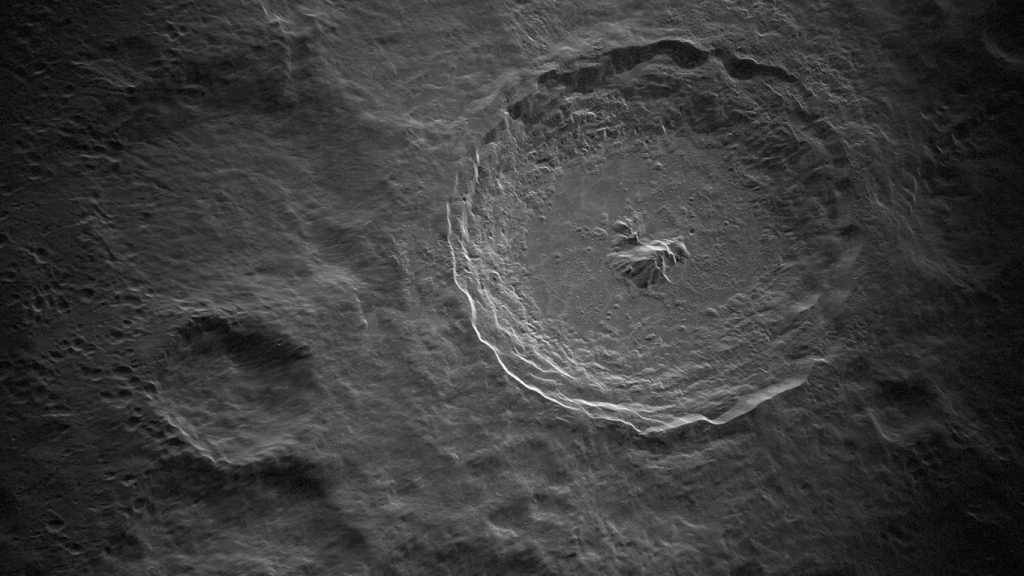

A partially processed view of the Tycho Crater, which was taken during a radar project by Green Bank Observatory, National Radio Astronomy Observatory and Raytheon Intelligence & Space using the Green Bank Telescope and antennas in the Very Long Baseline Array.

Credit: NRAO/GBO/Raytheon/NSF/AUI

Radio astronomy isn’t just about distant galaxies, it’s also helping us study our nearest neighbour, the Moon. A collaboration between Raytheon and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory has equipped the giant Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia with a radar transmitter that uses less power than a kitchen microwave, yet produces some of the most detailed 3D radar images of lunar features like Tycho Crater and Hadley Rille. Using the Moon as a testbed allows astronomers to refine techniques that could one day track asteroids, planetary moons, and even space debris a striking example of how cutting-edge technology is expanding our view of the cosmos.

News | The moon is a sight for scientific eyes at Raytheon | Raytheon

October Lunar Calendar

ctobers moon calendar from Sky View Café (skyviewcafe.com)

A full yearly lunar calendar can be found here :-

https://www.mooninfo.org/moon-phases/2025.html

Moon Feature

Shackleton Crater — A Gateway to the Moon’s Future

Shackleton Crater lies at the lunar south pole, right on the rim of the Moon’s axis of rotation. It’s about 21 km (13 miles) wide and over 4 km (2.5 miles) deep. Because the Sun never rises high at the poles, most of the crater floor is in permanent shadow some parts have likely been dark for billions of years.

The polar crater of the Moon. Source: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

Published the first image of the ShadowCam camera

This permanent darkness makes Shackleton fascinating for two reasons:

- Water Ice: The cold, shadowed floor is thought to trap water ice delivered by comets and asteroids over time. Data from spacecraft like NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and India’s Chandrayaan-1 have provided evidence of ice deposits there. Such ice could be a vital resource for future lunar explorers, providing drinking water, oxygen, and even rocket fuel.

- Peaks of Eternal Light: In contrast, the crater’s rim is almost constantly bathed in sunlight. These “peaks of eternal light” are rare on the Moon and could provide continuous solar power for future missions or lunar bases.

Because of this unique combination ice in the shadows, sunlight on the rim Shackleton is often mentioned as a prime location for future lunar bases. NASA’s Artemis program and other international efforts are eyeing the south pole region, with Shackleton as a top candidate.

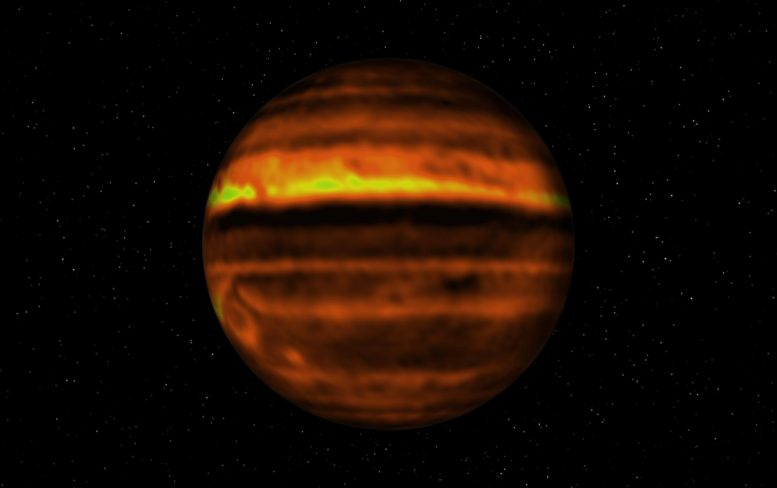

Planets

Spherical ALMA radio telescope map of Jupiter showing the distribution of ammonia gas below Jupiter’s cloud deck. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), I. de Pater et al.; NRAO/AUI NSF, S. Dagnello

Planetary Radio Astronomy

Planetary radio astronomy is the study of radio waves naturally emitted by planets and their magnetospheres. The field was born in 1955 with the surprising discovery that Jupiter is a powerful radio source. Since then, spacecraft like Voyager, Galileo, and Cassini have revealed that radio emissions are common across the giant planets, and even Earth, arising from energetic interactions between magnetic fields, plasma, and charged particles.

These radio waves are typically generated by a process known as the cyclotron maser instability. In this mechanism, energetic electrons spiral along magnetic field lines in auroral regions, transferring their energy into intense bursts of radio emission. At Jupiter, for instance, this creates spectacular decametric (DAM) emissions, strongly influenced by the volcanic moon Io, while Saturn produces its own distinct kilometric radio emissions (SKR), whose puzzling variability has been tracked by Cassini.

Radio astronomy allows scientists to probe deep into planetary magnetospheres and plasma environments in a way that optical telescopes cannot. It reveals rotational dynamics, auroral processes, and even interactions between planets and their moons. Looking further afield, the same principles are now being used in the search for radio signals from exoplanets. Although no confirmed detections exist yet, predictions suggest that “hot Jupiters” close to their stars could generate radio emissions far stronger than Jupiter’s. Detecting such signals would give us new ways to study alien magnetic fields, stellar winds, and even exomoon interactions.

But back to using our eyes and telescopes!

☀️ Mercury

Mercury is an evening planet this month, but it’s a poor showing from the UK. Even at greatest eastern elongation on 29th October (23.9° from the Sun), it remains low in bright twilight. On the 19th, Mercury sits close to Mars, but both are too low to be easily seen.

🟡 Venus

Venus shines brilliantly as the Morning Star in the east before sunrise. Early in the month it rises more than two hours before dawn, but by late October it’s closer to the Sun and much harder to spot. A highlight comes on the 19th, when a thin crescent Moon lies nearby, making a beautiful pairing in the pre-dawn sky.

🔴 Mars

Mars is technically an evening planet, but very faint and low in the twilight glow. It briefly passes close to Mercury on the 19th, but both are difficult targets this month. Best to wait for Mars to improve in 2026.

🟠 Jupiter

Jupiter dominates October nights. It brightens from magnitude –2.0 to –2.2 and climbs high in the south, reaching nearly 60° altitude by the end of the month

🪐 Saturn

Saturn remains well placed after its September opposition, visible most of the evening. It fades slightly from magnitude +0.2 to +0.4, but its biggest change is visual: the rings are now almost edge-on, giving the planet a slender, unusual look. A waxing gibbous Moon sits close on the 6th.

🔵 Uranus

Uranus climbs higher each night as it approaches its November opposition. At magnitude +5.6 it can just be glimpsed from a very dark site, but binoculars or a small telescope are best. It sits close to the Pleiades in Taurus throughout the month, offering a fine wide-field view.

🔷 Neptune

Neptune, just past its September opposition, is still well placed in Aquarius. At magnitude +7.8 it requires binoculars or a telescope to see, but it reaches a decent 36° above the southern horizon for UK observers.

Meteor Showers

WE’re used to watching meteor showers with their eyes, but you can also listen to them using ordinary FM radio signals. Here’s how it works:

When a meteor enters the Earth’s atmosphere, it burns up and leaves behind a trail of ionised gas. This plasma trail can act like a temporary mirror, reflecting radio waves back to Earth. This phenomenon is called meteor scatter.

If you tune an FM radio to a frequency where no local station is broadcasting (a “quiet” channel), you may occasionally hear brief bursts of distant radio stations suddenly coming through. Each burst corresponds to a meteor reflecting a signal from a transmitter that’s normally too far away to detect.

During a meteor shower like the Orionids or Perseids, the rate of these bursts increases dramatically. Listeners describe them as short snatches of music, speech, or static “pings” lasting from a fraction of a second to a few seconds. The stronger the meteor, the longer and clearer the burst.

Amateur radio enthusiasts sometimes use this technique with simple receivers or even software-defined radios (SDRs) connected to laptops, turning meteor showers into both a visual and an auditory experience.

Meteor showers to watch out for or listen to this month

Orionids

The biggest shower this month peaking on the night of the 21/22, but meteors are visible from the 2nd October-7th November. This is a good year to watch the debris from Halley’s Comet hitting the Earths atmosphere as the Moon sets at around 10pm making for darker skies.

Dracanids

Peaking on the night of the 8/9 this shower is also known as the Giacobinids, after the French astronomer Michel Giacobini who discovered the comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner1. This comet is the source of the dust and debris that create the meteors when they enter Earth’s atmosphere.

The radiant point is located in the constellation Draco, the dragon, which can be found in the northern sky. The moon will be a waning crescent and will not interfere much with the visibility of the meteors.

Comets

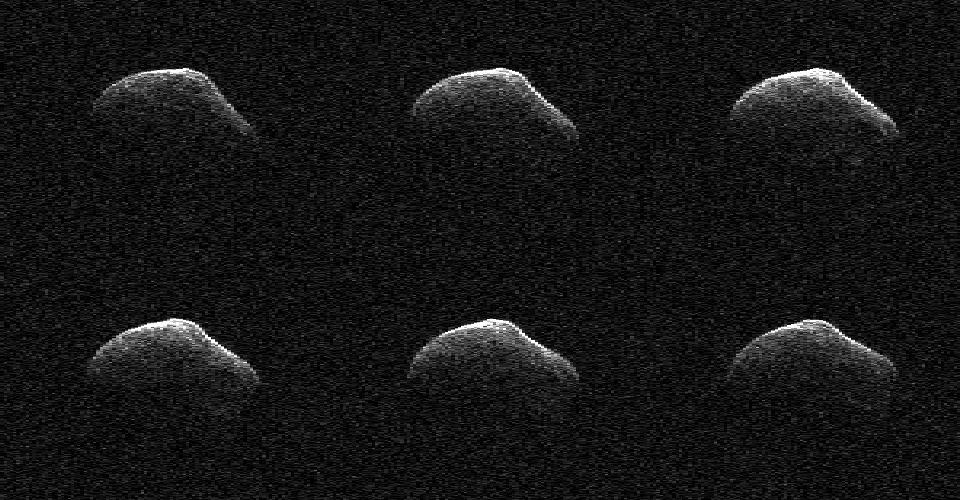

Comet Frozen In Time by NASA Radar

These radar images of comet P/2016 BA14 were taken on March 23, 2016, by scientists using an antenna of NASA’s Deep Space Network at Goldstone, California. At the time, the comet was about 2.2 million miles (3.6 million kilometers) from Earth. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/GSSR

Do Radio Astronomers Study Comets?

Absolutely. While comets are faint in visible light until they develop their tails, they can be studied very effectively with radio telescopes. Here’s how:

- Molecules in the Coma: As a comet approaches the Sun, its ices sublimate and release gas. Radio telescopes can detect the spectral lines of molecules like water (H₂O), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH₄), and ammonia (NH₃). These measurements tell us about the comet’s composition — in other words, what it’s made of.

- Water Production Rates: By measuring the intensity of specific emissions, astronomers can calculate how much water and gas the comet is producing each second. This is vital for understanding comet activity and evolution.

- Jets and Outgassing: High-resolution radio interferometers (like ALMA) can even map jets of gas streaming from a comet’s surface, showing how activity varies across its nucleus

- Origins of Organics: Some of the most complex organic molecules in the solar system have been identified in comets via radio astronomy, including glycine, an amino acid. This links comets with the possible origins of life.

- Radar Studies: Powerful planetary radars (like the Goldstone Solar System Radar or Arecibo when it was active) have been used to bounce signals off comet nuclei. These give direct information about a comet’s size, shape, and rotation.

More here:-

Comets at radio wavelengths – ScienceDirect

| Comet | Magnitude (approx.) | Altitude (°) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) | mag. 3–4 | 17–38 | Brightest comet of the month, potentially visible to the naked eye under dark skies. |

| C/2025 R2 (SWAN) | mag. 6–7 | 14–53 | A binocular comet, best seen in dark conditions. |

| 240P/NEAT | mag. 12 | 57 | Telescope required; moderately well placed in the sky. |

| C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) | mag. 8 | 25 | Good binocular/telescope target. |

| C/2024 E1 (Wierzchos) | mag. 11 | 42 | Telescope required. |

| C/2022 N2 (PanSTARRS) | mag. 13 | 11–82 | Faint, but at times placed high in the sky; requires a telescope. |

| 210P/Christensen | mag. 11 | 11 | Low on the horizon, challenging to spot. |

| 24P/Schaumasse | mag. 13 | 18–73 | Faint periodic comet; telescope only. |

| 414P/STEREO | mag. 12 | 1 | Very low and difficult to observe. |

| 3I/2025 N1 (ATLAS) | mag. 12 | 1 | Likely too faint and low for useful observation. |

Link here for further details of each comet and how to locate it.

Visual Comets in the Future (Northern Hemisphere) (aerith.net)

Deep Sky (DSO’s)

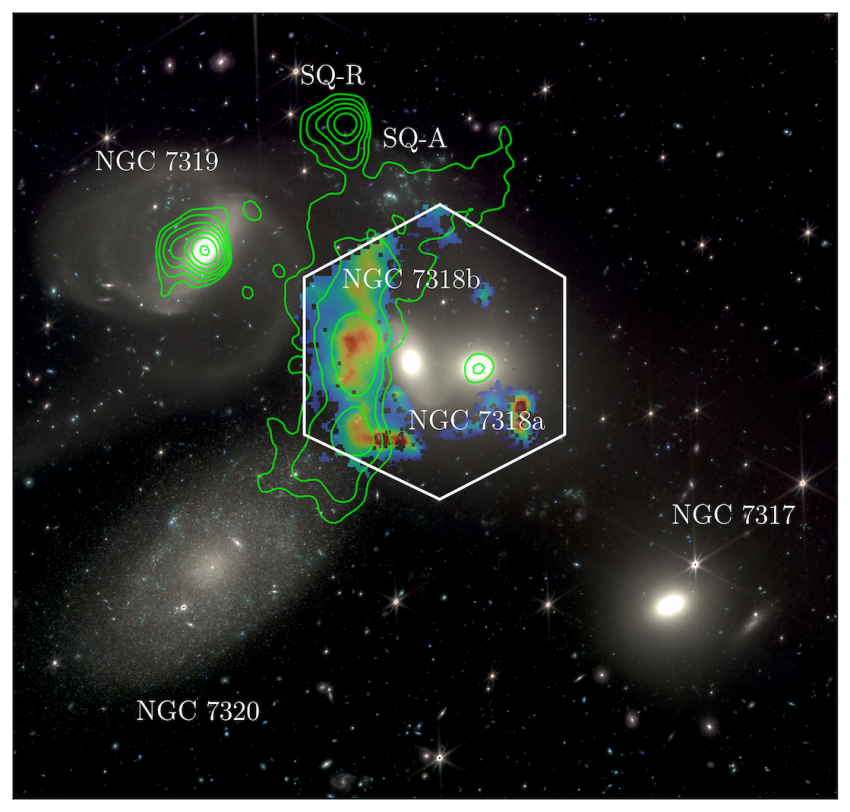

WEAVE data overlaid on a James Webb Space Telescope image of Stephan’s Quintet, with green contours showing radio data from the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) radio telescope. The orange and blue colours follow the brightness of Hydrogen-alpha obtained with the WEAVE LIFU, which trace where the intergalactic gas is ionised. The hexagon denotes the approximate coverage of the new WEAVE observations of the system, which is 36 kpc wide (similar in size to our own galaxy, the Milky Way).

University of Hertfordshire

Deep-sky observing is usually thought of as a visual or photographic pursuit, but radio astronomy has transformed our understanding of these same objects:

- Galaxies: Radio telescopes detect neutral hydrogen (H I) at 21 cm, mapping galaxy rotation and revealing dark matter through rotation curves.

- Radio Galaxies: Objects like Cygnus A and Inkathazo (32× the size of the Milky Way) were discovered through their colossal radio jets, invisible in optical light.

- Supernova Remnants: The Crab Nebula (M1) is a famous radio source, glowing across the spectrum from radio to gamma rays.

- Star-Forming Regions: Molecules such as CO are traced in the radio, showing where new stars are forming within nebulae invisible to optical observers.

In short, radio astronomy lets us see the energetic, hidden side of deep-sky objects from the gas fuelling star birth to the jets spewing from black holes.

Now these modern instruments produce vast amounts of data and need modern AI and machine learning techniques to cope with this vast amount of information and to produce useful science.

AI, Big Data, and the Radio Universe

Today’s radio astronomy is as much about handling information as it is about collecting it. Modern instruments such as LOFAR in Europe, MeerKAT in South Africa, and the upcoming Square Kilometre Array (SKA) generate data on a scale once unimaginable.

- LOFAR (Low-Frequency Array): Already processes tens of terabytes every day, with distributed antennas across Europe streaming data to central computers in the Netherlands.

- MeerKAT: Produces around 275 terabytes per day — the equivalent of 70,000 HD movies daily.

- SKA: When complete, it will be the largest science data project on Earth, generating up to 600 petabytes per year — more than the entire internet produced annually in the early 2000s.

This flood of information is impossible to manage manually, which is why AI and machine learning have become essential tools of the trade. They are used to:

- Classify galaxies neural networks (like the ClaRAN project) automatically sort radio galaxy shapes and morphologies, a job that would take humans decades.

- Find transients algorithms sift through the data stream to catch fleeting phenomena like fast radio bursts (FRBs) before they vanish.

- Filter noise distinguishing faint cosmic signals from radio frequency interference (RFI) caused by human technology.

- Sharpen images machine learning can produce super-resolution radio maps of jets, nebulae, and galaxies, pulling out detail that would otherwise be lost.

- Combine with citizen science projects like Radio Galaxy Zoo use human classifications to train AI, creating a feedback loop that improves both speed and accuracy.

In short, the next era of radio astronomy won’t just be defined by bigger telescopes — it will be defined by our ability to teach machines to listen with us.

Now onto this months DSO’s

🌌 Easy Deep-Sky Objects (Binoculars or Small Telescope)

- Andromeda Galaxy (M31) Visible with the naked eye from dark skies, spectacular in binoculars. Look for its bright oval glow high in the southeast.

- Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884, Perseus) Two sparkling clusters side by side, magnificent in binoculars.

- Owl Cluster (NGC 457, Cassiopeia) Small open cluster shaped like an owl with outstretched wings; easily seen in a small telescope.

- Triangulum Galaxy (M33) Large but faint spiral galaxy, best in binoculars under very dark skies.

- Blue Snowball (NGC 7662, Andromeda) Bright planetary nebula; small telescopes show a turquoise “disk” that stands out well.

🔭 Challenging Deep-Sky Objects (Medium / Large Telescope & Dark Skies)

- NGC 891 (Andromeda) A slim, edge-on spiral galaxy with a dark dust lane. Requires medium aperture and clear, dark conditions.

- Stephan’s Quintet (Pegasus) Famous compact galaxy group, visible as faint smudges in a 8-inch+ telescope. Imaging reveals interacting galaxies.

- NGC 7331 (Pegasus) Bright spiral galaxy, sometimes called the “Andromeda twin.” Nearby Stephan’s Quintet makes this a rewarding imaging field.

- Faint Taurus/Perseus Nebulosity — Wide-field imaging projects can capture the dark and dusty molecular clouds between Perseus and Taurus. Best for astrophotographers.

A little more about…

Stephan’s Quintet — A Galactic Gathering

Stephan’s Quintet in Pegasus is one of the sky’s most famous compact galaxy groups. Through a telescope, under good conditions, you’ll see a tight knot of fuzzy patches. In reality, these are five galaxies about 300 million light-years away (NGC 7317, 7318A, 7318B, 7319, and 7320), discovered by Édouard Stephan in 1877.

What makes this group fascinating is that four of the galaxies are physically interacting. They are locked in a slow-motion gravitational dance, colliding and tearing at each other with immense tidal forces. This interaction has sparked bursts of star formation, as gas clouds are shocked and compressed. The fifth member, NGC 7320, lies closer to us (≈40 million light-years) and is only a foreground galaxy, but it adds to the striking appearance.

Stephan’s Quintet is also famous in modern astronomy:

- It was one of the first images released by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2022, which revealed intricate filaments of dust, newborn stars, and even evidence of a giant shock wave where galaxies are colliding.

- In radio wavelengths, telescopes have traced vast clouds of neutral hydrogen gas stripped from the galaxies, showing how interactions can strip galaxies of their raw material for star formation.

ISS and other orbiting bits

🚀 ISS Overpasses

🛰 ISS Visible Passes – York, UK (October 2025)

| Date | Time (Start) | Brightness (mag) | Max Altitude | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15th | 06:52 | –0.5 | 11° | SSE → SE |

| 17th | 06:49 | –1.3 | 20° | SSW → E |

| 18th | 06:01 | –1.0 | 15° | S → ESE |

| 19th | 05:15 | –0.8 | 10° | SSE → SE |

| 19th | 06:48 | –2.2 | 33° | SW → E |

| 20th | 06:00 | –1.9 | 25° | SSW → E |

| 21st | 05:14 | –1.6 | 19° | SSE → E |

| 21st | 06:47 | –3.0 | 48° | WSW → E |

| 22nd | 06:00 | –2.8 | 40° | SSW → E |

| 23rd | 05:14 | –2.1 | 29° | SE → E |

| 23rd | 06:47 | –3.4 | 58° | WSW → E |

| 24th | 04:27 | –0.5 | 12° | E |

| 24th | 06:00 | –3.4 | 53° | SW → E |

| 25th | 05:13 | –2.3 | 34° | ESE → E |

| 25th | 06:46 | –3.4 | 56° | W → ESE |

| 26th | 03:26 | –0.4 | 11° | E |

| 26th | 04:59 | –3.5 | 58° | SW → ESE |

| 27th | 04:12 | –2.1 | 32° | ESE → E |

| 27th | 05:45 | –3.1 | 43° | W → ESE |

| 28th | 03:25 | –0.3 | 10° | E |

| 28th | 04:58 | –3.5 | 51° | SW → ESE |

| 29th | 04:11 | –1.8 | 26° | ESE → ESE |

| 29th | 05:44 | –2.5 | 29° | WSW → SE |

| 30th | 04:57 | –3.0 | 37° | SSW → SE |

Useful Resources

StarLust – A Website for People with a Passion for Astronomy, Stargazing, and Space Exploration.

http://www.n3kl.org/sun/noaa.html

http://skymaps.com/downloads.html

Astronomy Calendar of Celestial Events 2024 – Sea and Sky (seasky.org)

https://www.constellation-guide.com

IMO | International Meteor Organization

and of course the Sky at Night magazine!