A monthly look at astronomical events in the sky and on Earth

Compiled and written by Steve Sawyer

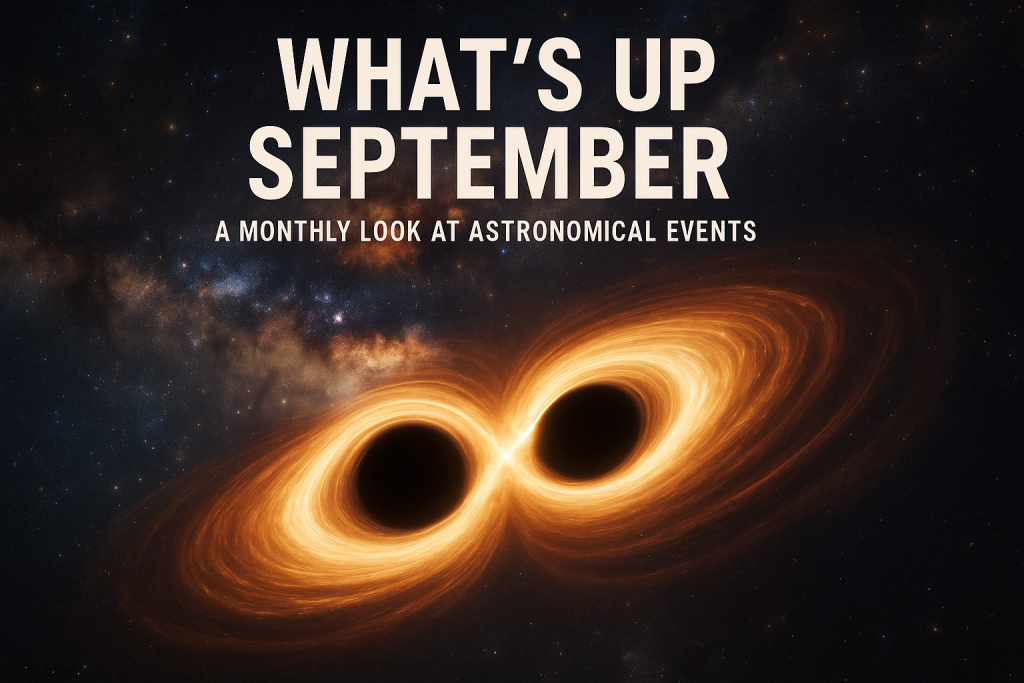

This month’s imagery takes us deep into the realm of cosmology, starting with a stunning simulation of two black holes merging—an immense event where their event horizons interact and distort space-time itself.

These cataclysmic collisions release powerful gravitational waves, ripples in space-time first predicted by Einstein and now routinely observed by ground-based detectors like LIGO and Virgo. To date, scientists have confirmed around 100 such events, primarily involving black holes and neutron stars.

However, Earth-based observatories are limited in sensitivity and range. Next-generation space-based gravitational wave missions, such as LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna), are scheduled for launch in the coming decade. These will be far more sensitive—capable of detecting lower-frequency waves from more distant and massive sources, including events like the one shown in the simulation below:

NASA SVS | Simulated Gravitational Wave All-Sky Image

Welcome to September’s What’s up!

As summer fades and autumn approaches, September welcomes the return of longer nights and with them, darker skies ideal for stargazing. The weeks around the equinox are often a prime time for spotting the aurora, especially during heightened solar activity. There’s also the added bonus of another lunar eclipse this time taking place in the evening, more on this later.

Here’s what’s up this month!

This Months and Upcoming York Astro Presentations

Upcoming events to put in your diary

| Date | Title | Speaker |

|---|---|---|

| 05/09/2025 | Discovering the Night Sky: Basic Astrophotography | Steve Bowden |

| 19/09/2025 | The Largest Telescope on Earth: From an Inch to Forty Metres | Jurgen Schmoll |

For further details see the events page Astronomy Presentations by guest speakers | York Astro and our Facebook group (20+) The York Astronomical Society Chat Group | Facebook

The Big Bang theory describes how the universe began about 13.8 billion years ago from an extremely hot, dense state that rapidly expanded and continues to grow today. Evidence for this origin includes the cosmic microwave background radiation, the faint afterglow still visible across the sky.

So what’s on this month?

With the autumnal equinox on the 22nd, longer nights return. Ursa Major sinks low in the north, while Arcturus and Boötes drift toward the horizon. Auriga climbs in the northeast, followed later by Taurus and Gemini. Andromeda stands high in the east, with Triangulum and Aries below. The Milky Way arches overhead—its star clouds most visible in Cassiopeia and Cygnus. The Double Cluster in Perseus is well placed, with Cepheus near the zenith and Draco and Hercules (home to M13) nearby.

The Summer Triangle dominates the southwest, while the Great Square of Pegasus rises in the southeast. Beneath it lie the zodiacal constellations Capricornus and Aquarius. Algedi and Dabih in Capricornus are naked-eye and binocular doubles, while Aquarius features the ‘Water Jar’ asterism. Fomalhaut in Piscis Austrinus shines below, marking where the mythical water stream ends. To the east, Pisces and its ‘Circlet’ asterism emerge, with Cetus hugging the horizon—home to Mira, a variable star that brightens and fades across weeks.

Sky Diary

This table captures the astronomical events for September, including phases of the moon, planetary alignments, and other notable occurrences.

| Date | Time (UTC) | Event Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sep 7 | 18:09 | Full Moon lights up the sky |

| Sep 7 | 18:12 | Total lunar eclipse, magnitude 1.362 |

| Sep 8 | 20:09 | Saturn (mag. 0.6) sits 4.0° south of the Moon |

| Sep 10 | 12:09 | Moon reaches perigee – closest to Earth at 364,781 km |

| Sep 12 | 21:48 | Pleiades passes just 1.0° south of the Moon |

| Sep 13 | 03:28 | Mars (mag. 1.6) pairs with Spica, 2.0° to the north |

| Sep 14 | 10:33 | Last Quarter Moon phase |

| Sep 16 | 11:06 | Jupiter (mag. -2.0) passes 4.6° south of the Moon |

| Sep 16 | 17:58 | Pollux sits 2.4° north of the Moon |

| Sep 19 | 08:57 | Venus (mag. -3.9) meets Regulus just 0.4° to the north |

| Sep 19 | 11:11 | Regulus lies 1.3° south of the Moon |

| Sep 19 | 11:46 | Venus (mag. -3.9) passes 0.8° south of the Moon – occultation visible from parts of Europe |

| Sep 21 | 05:00 | Saturn reaches opposition – its best viewing of the year |

| Sep 21 | 19:42 | Partial solar eclipse, magnitude 0.855 |

| Sep 21 | 19:54 | New Moon marks the start of a new lunar cycle |

| Sep 22 | 18:20 | Autumn Equinox – day and night are nearly equal |

| Sep 23 | 11:00 | Neptune at opposition (mag. 7.7), brightest of the year |

| Sep 23 | 21:31 | Spica passes 1.1° north of the Moon |

| Sep 24 | 14:50 | Mars (mag. 1.6) appears 3.9° north of the Moon |

| Sep 26 | 09:46 | Moon reaches apogee – farthest from Earth at 405,552 km |

| Sep 27 | 17:34 | Antares lies just 0.6° north of the Moon |

| Sep 29 | 23:54 | First Quarter Moon – half-illuminated and rising early evening |

Sky Maps

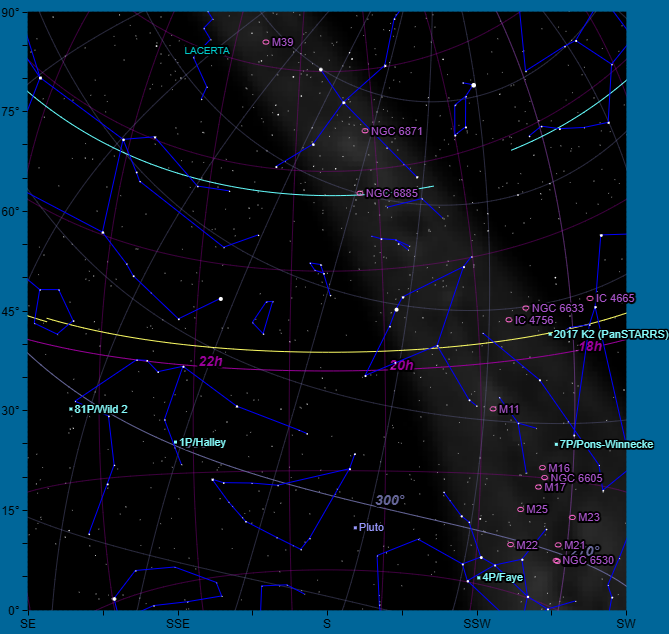

Looking South on the 15th at 22:00

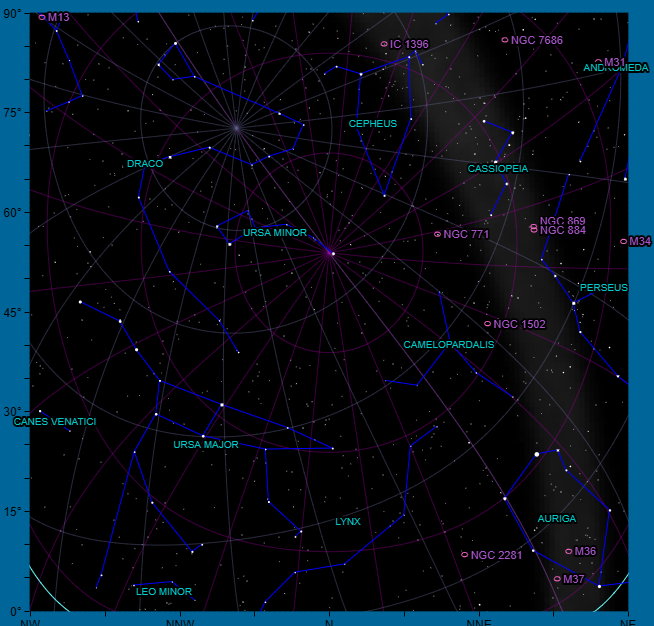

Looking North on the 15th at 22:00

he two charts above show all DSOs of magnitude 6.0 or brighter. They are both taken from

SkyViewCafe.com and correct for the 15th of the month. For a clickable list of Messier objects with images, use the Wikipedia link.

Septembers Objects

The Sun

The Sun is powered by nuclear fusion in its core, where hydrogen atoms combine to form helium, releasing enormous amounts of energy. This energy moves outward through the Sun’s layers and eventually radiates into space as sunlight, heat, and streams of charged particles that shape space weather.

☀️ September 2025 Solar Forecast

As we head into September, solar activity shows some ups and downs. The 10.7 cm radio flux starts fairly high near 155 but gradually dips to around 115 by mid-month before rising again to 150 by the 20th, reflecting changing sunspot activity.

Geomagnetic conditions remain mostly quiet to unsettled early on (Kp 2–3), but a notable disturbance is predicted around September 4–6, when geomagnetic activity could spike to Kp 5–6 — a level capable of producing moderate aurora displays at higher latitudes. A smaller rise in activity is expected again around September 15, with Kp reaching 5.

In summary:

- Early September (1–3): Calm, with quiet skies.

- September 4–6: Active period, possible aurora events.

- September 7–14: Generally quiet, low geomagnetic activity.

- September 15: Another brief disturbance, aurora possible.

- September 16–20: Activity steadies, with mild to moderate fluctuations.

Overall, September offers mostly stable solar conditions, but with two promising windows (4–6 and 15 September) when aurora-watchers may want to keep an eye on the skies.

Auroa Forecasts

A bit US centred but still useful

Aurora Dashboard (Experimental) | NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center

And our own Met-office have an excellent space weather forecast page here Space Weather – Met Office

The Moon

The Moon is shown in its fiery infancy, glowing with molten rock as it emerges from the debris of a colossal collision with the early Earth. Streams of incandescent material arc across space, capturing the dramatic and awe-inspiring birth of our nearest neighbour.

This September opens with a total lunar eclipse on the evening of the 7th, visible from Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Maximum eclipse occurs at 18:12 UT, with the Moon spending around 1 hour 22 minutes fully immersed in Earth’s umbra. During totality, the Moon should glow a deep red-orange, depending on atmospheric conditions.

This eclipse coincides with the Harvest Moon—the full Moon closest to the September equinox.

The Harvest Moon is the full Moon that falls closest to the autumnal equinox, which occurs between 21–23 September in the Northern Hemisphere. At this time of year, the Moon’s path along the ecliptic makes a shallow angle with the horizon, causing it to rise soon after sunset for several evenings in a row.

Normally, the Moon rises about 50 minutes later each night, but around the Harvest Moon this gap shrinks to just 20–30 minutes. The result is a string of bright, early-rising full Moon nights that once gave farmers valuable extra light to bring in their crops.

Because the Harvest Moon climbs low along the horizon, it often appears larger and glows with a warm orange or red tint. This effect is caused by the Moon’s light filtering through more of Earth’s atmosphere, scattering away blues and greens and leaving the longer red wavelengths to dominate.

Beyond the eclipse, the Moon puts on more shows this month:

- 12 September – The waning gibbous Moon passes across the Pleiades, creating a striking occultation.

- 19 September – A spectacular triple conjunction occurs as the crescent Moon occults Venus and Regulus in turn, an event best seen from high northern latitudes.

- 23 & 27 September – The Moon occults Spica (Virgo) and later Antares (Scorpius), with both stars briefly vanishing behind the lunar limb.

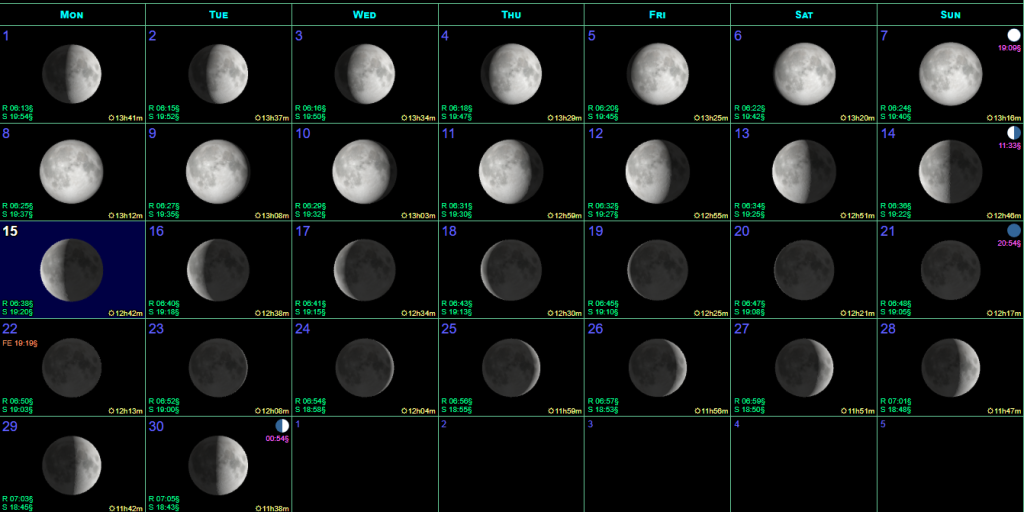

September Lunar Calendar

Septembers moon calendar from Sky View Café (skyviewcafe.com)

A full yearly lunar calendar can be found here :-

https://www.mooninfo.org/moon-phases/2025.html

Moon Feature

🌙 Messier & Messier A

Unlike most lunar craters, Messier is elongated, looking more like a rugby ball than a circle. Just beside it sits Messier A, a more rounded companion. Their odd pairing is thought to be the result of a glancing impact, where the incoming object struck the Moon at a very low angle, skipped, and created two separate craters.

The “Comet’s Tail”: Extending eastward from Messier A is a striking set of parallel rays of ejected material, often called the Comet’s Tail. These bright streaks make the site stand out even at Full Moon, when most surface relief is washed out.

The pair is best seen a few days after New Moon, when Mare Fecunditatis lies near the terminator and the low Sun angle makes their unique shapes more obvious. Under higher illumination (near Full Moon), the rays become especially bright.

To spot Messier and Messier A, start with the prominent dark oval of Mare Crisium (the “Sea of Crises”) on the Moon’s eastern edge. From Crisium, look south toward the large, bright crater Langrenus with its sharp rim and central peak. Just west of Langrenus lies Mare Fecunditatis (“Sea of Fertility”), where you’ll find the small, twin Messier craters near the mare’s centre.

Planets

This image captures the violent beauty of the early solar system, with a blazing young Sun surrounded by a swirling disk of gas and dust. Within the chaos, fiery protoplanets collide and merge, laying the foundations for the worlds we know today.

☀️ Mercury

Best seen at the start of the month, rising about 30 minutes before sunrise. On 1 September it shines at magnitude –1.8 in Leo, but it quickly slips closer to the Sun and becomes hard to spot after mid-month.

🟡 Venus

Visible as a brilliant morning star (magnitude –3.8) in Leo. On 19 September it sits near the Beehive Cluster before being occulted by the Moon. It remains a dazzling sight before sunrise throughout the month.

🔴 Mars

Not visible this month.

🟠 Jupiter

A bright morning object in Taurus, reaching magnitude –5.8 by the end of September. It stands near the Pleiades, with excellent visibility before dawn.

🪐 Saturn

The star of the month! Saturn reaches opposition on 21 September, shining at magnitude +0.2 in Pisces. At its best and brightest for the year, it’s visible all night, with its rings and moons rewarding even modest telescopes.

🔵 Uranus

Visible in Taurus, shining at magnitude +5.8. It sits 4.5° south of the Pleiades and is best observed later in the night.

🔷 Neptune

Reaches opposition on 23 September in Pisces, glowing faintly at magnitude +7.8.

Meteor Showers

From orbit, Earth’s atmosphere glows as meteors burn in fiery arcs across the night side.

September is relatively quiet for meteors compared with the Perseid-rich nights of August, but there are still a couple of showers worth noting. The Kappa Cygnids linger into the first few nights of the month, though activity is low (just a handful of meteors per hour) and this year the Moon will interfere with viewing.

More significantly, the Southern Taurids get underway from 10 September, stretching well into November. While never especially active, averaging 5–10 slow meteors per hour, the Taurids are famous for their bright fireballs, which can appear at any time during their long season.

🔭 Viewing Tips:

- Best seen after midnight, when the radiant in Taurus has climbed higher into the sky.

- Look toward the eastern and southern skies, but keep your gaze relaxed and wide — Taurid meteors can appear almost anywhere.

- Try to observe from a dark-sky location, away from artificial lights, and allow your eyes 20–30 minutes to adjust fully to the dark.

Comets

Icy cliffs and jets of vapor burst into life as the comet nears the Sun.

| Comet | Approx. Mag | Viewing Details & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) | ~10 | Now brighter than in August, visible in the morning sky. A faint but rewarding telescopic target, best seen with 200 mm+ instruments. |

| C/2024 E1 (Wierzchos) | ~12 | Still faint at mag 12, located in the morning sky. Requires a telescope or long-exposure imaging; binoculars won’t pick it up. |

| C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) | ~8 → 7 | Brightening steadily this month, potentially a highlight of the autumn. Low in the pre-dawn sky, and expected to improve as it approaches perihelion in October. |

| 240P/NEAT | ~12 | A periodic comet, holding steady around magnitude 12. Observable in larger amateur telescopes; faint coma with little tail activity. |

| 414P/STEREO | ~12 | Recently recovered, about magnitude 12. Visible before dawn with moderate telescopes; best tracked using detailed charts. |

| 3I/2025 N1 (ATLAS) | ~12 | A rare interstellar comet passing through the solar system. Around mag 12, accessible to telescopes under dark skies. |

| C/2022 N2 (PANSTARRS) | ~13 | Very faint at mag 13, only visible with larger telescopes (≥300 mm). A low-surface brightness object, best suited to astrophotography. |

| 210P/Christensen | ~13 | Periodic comet at magnitude 13, observable with medium-sized telescopes. Compact coma but requires careful tracking. |

Link here for further details of each comet and how to locate it.

Visual Comets in the Future (Northern Hemisphere) (aerith.net)

Deep Sky (DSO’s)

Here we see the blazing core of a spiral galaxy, where jets from a central black hole pierce space and spiral arms sweep outward into the distance. Clusters of new-born stars and faint globular clusters shimmer across the image.

Easy & Rewarding Targets

| Object | Type | Approx. Mag | Viewing Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andromeda Galaxy (M31) | Spiral Galaxy | 3.4 | Naked-eye in dark skies; binoculars show elongated core with companions M32 and M110. High in the east by mid-evening. |

| Triangulum Galaxy (M33) | Spiral Galaxy | 5.7 | Large but faint; best in dark skies with wide-field binoculars or telescope. |

| Double Cluster (NGC 869/884) | Open Clusters | 4.3 / 4.4 | Striking twin clusters between Perseus & Cassiopeia. Superb in binoculars. |

| Great Hercules Cluster (M13) | Globular Cluster | 5.8 | Early evening object in Hercules; bright, compact, and rich in stars. |

| Wild Duck Cluster (M11) | Open Cluster | 5.8 | Dense, fan-shaped cluster in Scutum. Best before it sets earlier in the night. |

| Owl Cluster (NGC 457) | Open Cluster | 6.4 | Fun “owl/ET” shape in Cassiopeia; easy binocular/telescope target. |

Advanced & Challenging Targets

| Object | Type | Approx. Mag | Viewing Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stephan’s Quintet (HCG 92) | Galaxy Group | 12–13 | Famous group of five galaxies in Pegasus. Needs 20 cm+ telescope and very dark skies. |

| NGC 7331 (Pegasus) | Spiral Galaxy | 9.5 | Sometimes called the “Mini-Andromeda.” Next to Stephan’s Quintet; faint but rewarding. |

| Blue Snowball (NGC 7662) | Planetary Nebula | 9 | Tiny bluish disk in Andromeda; looks stellar at low power, resolves with high magnification. |

| Bubble Nebula (NGC 7635) | Emission Nebula | 10 | Small but distinctive; filters help reveal the bubble shape. Near cluster M52 in Cassiopeia. |

| Pacman Nebula (NGC 281) | Emission Nebula | 7.4 (faint) | In Cassiopeia; requires dark skies and a filter to bring out detail. |

| Cave Nebula (Sh2-155) | Emission Nebula | Very faint | In Cepheus; extremely challenging visually, better for astrophotography. |

ISS and other orbiting bits

🚀 ISS Overpasses

🛰 ISS Visible Passes – York, UK (September 2025)

| Date | Brightness (mag) | Start (Time, Alt, Az) | Highest Point (Time, Alt, Az) | End (Time, Alt, Az) | Pass Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 Aug | -3.7 | 03:54:10, 57° S | 03:54:19, 58° S | 03:57:38, 10° E | visible |

| 31 Aug | -3.2 | 05:27:36, 10° W | 05:30:49, 42° SSW | 05:34:01, 10° SE | visible |

| 01 Sep | -1.8 | 03:07:30, 23° ESE | 03:07:30, 23° ESE | 03:08:58, 10° E | visible |

| 01 Sep | -3.5 | 04:40:24, 23° WSW | 04:42:12, 49° SSW | 04:45:29, 10° ESE | visible |

| 02 Sep | -3.6 | 03:53:49, 53° SSE | 03:53:49, 53° SSE | 03:56:51, 10° ESE | visible |

| 02 Sep | -2.6 | 05:27:01, 10° W | 05:29:56, 27° SSW | 05:32:49, 10° SSE | visible |

| 03 Sep | -1.3 | 03:07:22, 16° ESE | 03:07:22, 16° ESE | 03:08:11, 10° ESE | visible |

| 03 Sep | -3.1 | 04:40:16, 27° WSW | 04:41:19, 35° SSW | 04:44:25, 10° SE | visible |

| 04 Sep | -2.4 | 03:54:00, 28° SE | 03:54:00, 28° SE | 03:55:53, 10° ESE | visible |

| 04 Sep | -2.0 | 05:26:55, 11° WSW | 05:28:49, 16° SW | 05:30:57, 10° S | visible |

| 05 Sep | -2.2 | 04:40:54, 20° SSW | 04:40:54, 20° SSW | 04:42:52, 10° SSE | visible |

| 10 Sep | -1.6 | 20:33:58, 10° SSE | 20:35:11, 12° SE | 20:35:12, 12° SE | visible |

| 10 Sep | -0.9 | 22:08:05, 10° SW | 22:08:06, 10° SW | 22:08:06, 10° SW | visible |

| 11 Sep | -2.5 | 21:19:28, 10° SW | 21:21:40, 25° S | 21:21:40, 25° S | visible |

| 12 Sep | -2.3 | 20:31:00, 10° SSW | 20:33:35, 21° SSE | 20:34:59, 16° ESE | visible |

| 12 Sep | -1.7 | 22:06:35, 10° WSW | 22:07:53, 21° WSW | 22:07:53, 21° WSW | visible |

| 13 Sep | -3.4 | 21:17:45, 10° SW | 21:20:57, 42° SSE | 21:21:01, 42° SSE | visible |

| 14 Sep | -2.9 | 20:28:59, 10° SW | 20:32:03, 34° SSE | 20:34:02, 18° ESE | visible |

| 14 Sep | -2.1 | 22:05:10, 10° WSW | 22:06:54, 27° WSW | 22:06:54, 27° WSW | visible |

| 15 Sep | -3.7 | 21:16:13, 10° WSW | 21:19:30, 55° S | 21:19:48, 52° SSE | visible |

| 16 Sep | -3.4 | 20:27:17, 10° WSW | 20:30:31, 48° SSE | 20:32:38, 19° E | visible |

| 16 Sep | -2.0 | 22:03:44, 10° W | 22:05:29, 27° WSW | 22:05:29, 27° WSW | visible |

| 17 Sep | -3.7 | 21:14:41, 10° W | 21:18:00, 58° S | 21:18:15, 56° SSE | visible |

| 18 Sep | -3.6 | 20:25:39, 10° WSW | 20:28:57, 58° S | 20:30:58, 21° ESE | visible |

| 18 Sep | -1.8 | 22:02:15, 10° W | 22:03:49, 24° WSW | 22:03:49, 24° WSW | visible |

| 19 Sep | -3.5 | 21:13:08, 10° W | 21:16:23, 50° SSW | 21:16:30, 49° S | visible |

| 20 Sep | -3.5 | 20:24:01, 10° W | 20:27:19, 56° S | 20:29:10, 23° ESE | visible |

| 20 Sep | -1.4 | 22:00:46, 10° W | 22:02:01, 18° WSW | 22:02:01, 18° WSW | visible |

| 21 Sep | -2.8 | 21:11:32, 10° W | 21:14:38, 35° SSW | 21:14:40, 35° SSW | visible |

| 22 Sep | -3.1 | 20:22:21, 10° W | 20:25:33, 44° SSW | 20:27:20, 22° SE | visible |

| 22 Sep | -0.9 | 21:59:31, 10° WSW | 22:00:10, 13° WSW | 22:00:10, 13° WSW | visible |

| 23 Sep | -3.2 | 19:33:09, 10° W | 19:36:25, 51° S | 19:39:40, 10° ESE | visible |

| 23 Sep | -2.0 | 21:10:01, 10° W | 21:12:40, 22° SSW | 21:12:50, 22° SSW | visible |

| 24 Sep | -2.3 | 20:20:39, 10° W | 20:23:37, 29° SSW | 20:25:32, 17° SSE | visible |

| 25 Sep | -2.6 | 19:31:21, 10° W | 19:34:28, 37° SSW | 19:37:36, 10° SE | visible |

| 25 Sep | -1.2 | 21:09:00, 10° WSW | 21:10:30, 13° SW | 21:11:06, 12° SSW | visible |

| 26 Sep | -1.4 | 20:19:08, 10° WSW | 20:21:28, 18° SSW | 20:23:47, 10° S | visible |

| 27 Sep | -1.8 | 19:29:36, 10° W | 19:32:21, 24° SSW | 19:35:06, 10° SSE | visible |

| 29 Sep | -1.0 | 19:28:14, 10° WSW | 19:30:01, 14° SW | 19:31:48, 10° S | visible |

Useful Resources

StarLust – A Website for People with a Passion for Astronomy, Stargazing, and Space Exploration.

http://www.n3kl.org/sun/noaa.html

http://skymaps.com/downloads.html

Astronomy Calendar of Celestial Events 2024 – Sea and Sky (seasky.org)

https://www.constellation-guide.com

IMO | International Meteor Organization

and of course the Sky at Night magazine!

Brilliant Steve!